Vision

Aboriginal culture and heritage is protected and Traditional Owner led practices are embedded in the management and healing of Country.

Scope

All tangible and intangible Aboriginal culture and heritage that has recognised cultural, historical or spiritual significance; and Traditional Ecological Knowledge rejuvenation, protection and application in cultural landscapes management.

The region’s rich and diverse Aboriginal culture and heritage has been formed through the historical and spiritual significance of sites associated with human occupation spanning thousands of years, together with the enduring connection Traditional Owners/First Peoples have with Mallee landscapes.

The oldest dated Aboriginal heritage site in the Mallee region is located at Direl (Lake Tyrrell), with human activity recorded as far back as between 26,600 and 32,000 years ago, although use of the site was possibly as early as 45,000 years ago (51).

The first inhabitants of our region were numerous Aboriginal tribes of different language groups, including; Ngintait, Ngarkat, Latji Latji, Nyeri, Wergaia, Wadi, Wemba Wamba, Jari Jari, and Tati Tati. Given the semi-arid climate of the region, ready access to more permanent water has been a major determinant of human habitation, and as such the highest density of identified Aboriginal cultural heritage sites are located around, or close to areas of freshwater sources.

The Murray River and its associated lakes and waterways were important habitation areas for many Aboriginal groups, as the abundance of food, water and shelter allowed for more permanent occupation. The high number of cultural sites throughout the Murray floodplain is unique in Victoria, both for their concentration and diversity; including large numbers of burials, middens and hearth sites. There are also numerous meeting and ceremonial places, scarred trees, and artefact sites located across this landscape.

In the south of the region, freshwater lakes, streams and wetlands were focal points for Traditional Owners. Many lakes were the sites of large gatherings of several family groups that afforded trade and cultural exchanges. Direl (Lake Tyrrell) for example is identified by Traditional Owners as having unique spiritual and social values; with Dreamtime viewed and experienced in both the night sky and its reflections on the lake.

Intangible cultural heritage is integral to these landscapes, including the traditional knowledge, practice and expressions (e.g. biocultural knowledge, ceremonies, language, dance, song, and stories) passed down from generation to generation. Natural elements of the landscape such as landforms, flora and fauna can also have particular significance to Traditional Owners.

The Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 provides for the protection of cultural heritage in Victoria, covering both tangible and intangible heritage. The Aboriginal Heritage Regulations 2018 give effect to the Act, defining ‘areas of cultural heritage sensitivity’ and ‘high impact activities’; and setting out the circumstances in which a Cultural Heritage Management Plan (CHMP) should be prepared.

Traditional Owners, as Registered Aboriginal Parties (RAPs), have cultural heritage responsibilities under the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006. These include the evaluation of CHMPs and decisions about cultural heritage permit applications. There are currently two RAPs who represent the interests of Traditional Owners in their respective Country areas across the Mallee: Barengi Gadjin Land Council Aboriginal Corporation (BGLC) and First People of the Millewa Mallee Aboriginal Corporation (FPMMAC). Provisions are also made for Traditional Owners in non-RAP areas to be engaged in cultural heritage protection and management processes (see Section 1.2 for further detail on the region’s Traditional Owners).

For many thousands of years, the Country was managed and cared for by local First Peoples. As custodians of the oldest living culture in the world, Traditional Owners have always understood the responsibility that comes with looking after, and speaking for the Country of their ancestors and future generations. Cultural landscapes are fundamental to Country and the cultural identity of First Peoples. Caring for and healing Country with traditional ecological knowledge and customs built over thousands of years of practice is integral to this connection.

Cultural landscapes encompass both the material and symbolic, including Traditional Owner societies’ unique worldview, ontology, history, institutions, practices and the networks of relationships between humans, animals, plants, ancestors, song lines, physical structures, trade routes and other significant cultural connections to Country. Cultural landscapes reflect the management and modification of Country over many thousands of generations to provide maximum benefit to all of the inhabitants of Country, both human and non-human (52).

Regard for data sovereignty is fundamental to both traditional practice and cultural landscapes. Specifically, that Traditional Owner rights to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as their right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over these is recognised and meaningfully applied (53).

(51) Richards et al. (2007), Box Gully: new evidence for Aboriginal occupation of Australia south of the Murray River prior to the last glacial maximum, Archeology in Oceania 42 1-11.

(52) Victorian Traditional Owner Cultural Landscapes Strategy, 2021. Victorian Traditional Owner Corporations.

(53) Kukutai, T. Taylor, J. (Ed.). (2016) Indigenous data sovereignty: toward an agenda. ANU Press.

This section provides an overview on the current condition of Culture and Heritage in the Mallee. Regional indicators have been applied to establish a baseline, and where available identify long term trends, from which progress against our medium-term (6-year) and long-term outcome targets for Culture and Heritage can be determined.

As no regional-scale baseline information currently exists on the condition of the region’s Culture and Heritage assets, proxy condition indicators have been established using the assumption that being listed on the relevant heritage register affords some level of protection, and similarly, if sites are captured within a Co-management Agreement or a CHMP, the asset is protected through associated threat mitigation activities.

The Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Register and Information System (ACHRIS) is a central repository for information about cultural heritage. This includes the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Register which records cultural heritage place registrations, intangible heritage registrations and agreements, and approved CHMPs. Over 39,000 Aboriginal objects and places have been recorded on the register in Victoria to date, and, given these reflect locations where associated surveys have been undertaken, it is likely that this represents only a small proportion of such sites.

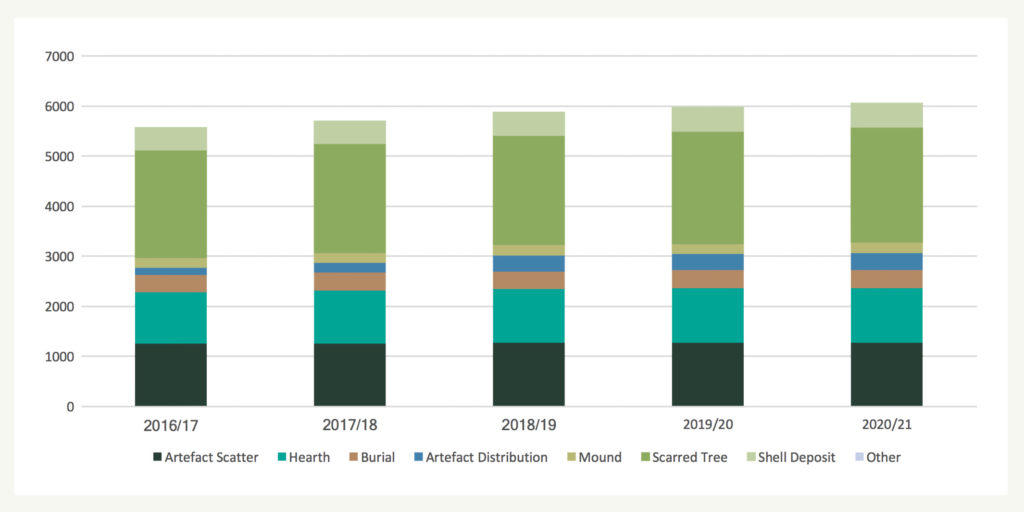

There are 4,463 Registered Aboriginal Places in the Mallee, a four percent (189) increase since 2016–17. These Places were comprised of 6,214 individual components in 2020–21, a nine percent (543) increase since 2016–17. Registered components are primarily comprised of Scarred Tree (2,291), Artefact Scatter (1,262), and Hearth (1,094) (Figure 34). There are currently no intangible cultural heritage registrations in the Mallee.

CHMP’s are prepared by a Heritage Advisor, setting out the results of an assessment on the potential impact of a proposed activity on Aboriginal cultural heritage. It outlines measures to be taken before, during and after an activity, in order to manage and protect Aboriginal cultural heritage in the activity area. A CHMP is required when a ‘high impact activity’ is planned in an area of ‘cultural heritage sensitivity’, as defined in the Aboriginal Heritage Regulations 2018.

There are currently 116 CHMPs within the Mallee that have been approved and lodged with First Peoples – State Relations, and a further 32 in preparation. In total, these CHMPs cover 58,900 hectares, a 58 percent (21,734 ha) increase since 2017–18 (Figure 35).

This section outlines the major threats and drivers of change influencing the condition and management of Culture and Heritage in the Mallee; core management and strategic directions that will guide delivery of our related actions over the next 6-years; and the associated regulatory, policy and planning framework that informed their development.

Major threats and key drivers of change

Aboriginal Culture and Heritage is inextricably connected to natural landscapes, and as such is vulnerable to the same suite of threatening processes. Altered hydrological regimes, for example, may expose sites on floodplains to longer periods of inundation and/or drying. Similarly, soil erosion can have a number of impacts through exposure of burial sites.

Efforts to protect our natural values from key threatening processes can also pose significant risks to cultural sites, particularly where soil disturbance is required (e.g. built infrastructure, invasive species management, and revegetation). Protecting and managing cultural heritage sites (i.e. compliance with the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 and associated Regulations) as an integral component of all land, water and biodiversity management processes is central to addressing this risk.

Further detail on the challenges, opportunities and major threats influencing the region’s natural landscapes, and therefore culture and heritage is provided in Section 1 (The Region – 4: Key Drivers of Change).

There is a growing recognition of the need to address the loss of traditional knowledge, cultural practice, and social connections resulting from Traditional Owners being disconnected from Country and prevented from pursuing traditional practices. In considering regional approaches to supporting Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples rights to self-determination and inherent obligations to continually speak for and look after the Country, it is essential the aspirations and concerns of key stakeholders are identified. Feedback provided at workshops, meetings, and on-Country events with Traditional Owners/First Peoples on how the RCS can support Traditional Owner led management of cultural landscapes included:

- It’s important to recognise links between healthy Country and healing and wellbeing for First Nations Peoples, including economic wellbeing

- First Nations communities bring diverse life experiences and connections to these cultural landscapes and special places

- First Nations Peoples manage Country holistically to address multiple values and objectives, healing both Country and culture. It is important that ecosystems and parts of Country (both material and symbolic) are recognised as connected, not separate, cultural landscapes

- The region’s natural landscapes are fundamental to Country and the cultural identity of First Peoples. Caring for and healing Country with traditional ecological knowledge and customs built over thousands of years of practice is integral to this connection.

Holistic management of Country as ‘cultural landscapes’ was a key point raised throughout consultation processes. Particularly with regard to the way in which the framework applied by this RCS does not support whole-of-landscape connections (i.e. the separation of landscapes into themes, the prioritisation of specific assets over others, and the identification of ‘delivery’ landscapes (i.e. Local Areas) based primarily on ecological processes/similarities). Exploring how cultural landscapes and values can inform planning and delivery approaches was identified as an opportunity for improvement by some groups.

Overall, increased support for Traditional Owner/First Peoples expertise in caring for and healing Country to provide ongoing ecological benefits and enhanced connections with Country was a priority shared by all groups. Opportunities for the application of traditional ecological knowledge included:

- Greater involvement in water planning decisions and delivery processes, including the incorporation of cultural flows into waterway management activities

- Re-introducing traditional burning and other cultural healing practices

- Restoring native plant and animal communities

- Protecting species of cultural importance and returning them to the landscape

- Applying restorative farming practices

- Rehabilitating significant cultural sites

- Supporting Indigenous rangers to work on-Country

- Expanding traditional languages knowledge and use

- Creating educational and interpretive opportunities to share culture.

Integration of Traditional Owner/First Peoples aspirations and priorities into regional delivery models will also contribute to desired outcomes established by the RCS for Community Capacity for NRM, and ultimately support the protection and enhancement of the region’s natural landscapes (i.e. Biodiversity and Waterways).

Aligned plans

Identification of the priority management and strategic directions detailed below has been informed by federal and state legislation, policies and strategies; regional strategies and action plans; and stakeholder priorities. The primary federal, state and regional instruments considered through this process are detailed in Appendix 2.

As there is currently no overarching ‘whole-of-region’ plan that collates strategic directions, priorities and targets for the protection and application of Culture and Heritage in the Mallee, the following state based strategic frameworks were applied, where appropriate, to help inform our regional approach:

- The Victorian Traditional Owner Cultural Landscapes Strategy (2021) sets out a framework to enable and empower Traditional Owners to lead the planning and management of cultural landscapes according to cultural objectives. This framework was collaboratively designed by, and for, Traditional Owners. It is intended to act as a thematic toolkit that can be adapted to each group’s self-determined pathway for healing and caring for Country. The Framework has five Program Components describing 10-year objectives for: restoring the Traditional Owner knowledge system; strengthening Traditional Owner resilience; enabling Traditional Owner cultural landscape planning; embedding Traditional Owner knowledge and practice into policy, planning and management of Country; and enabling Traditional Owners to apply cultural objectives, knowledge and practice in the management of public land

- Pupangarli Marnmarnepu ‘Owning Our Future’ Aboriginal Self-Determination Reform Strategy 2020-2025, was developed by DELWP to align with whole-of-government commitments set out in the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework (VAAF) and the VAAF Self-Determination Reform Framework. This guides government and agencies to enable action towards Aboriginal self-determination. From an NRM perspective, this means empowering Traditional Owners to participate and lead, if and how they choose; efforts to manage and heal Country.

The overall objectives and priorities set out by Traditional Owner Plans (e.g. BGLC’s Growing What is Good Country Plan — Voices of the Wotjobaluk Nations and FPMMAC’s Country-Culture-People Action Plan) have also informed development of regional priorities and desired outcomes for Culture and Heritage. Specific place and/or activity- based priorities established by these and other Plans (e.g. Victorian Traditional Owner Cultural Fire and Native Foods and Botanicals Strategies) are considered within the associated ‘Local Area’ (see Section 4).

Management directions

In considering the current condition of Aboriginal Culture and Heritage in the Mallee; key drivers influencing this condition; associated planning instruments; and stakeholder priorities; two key principles to inform our efforts have been identified. Specifically, that regional NRM programs collectively support:

- Protection of Aboriginal culture and heritage, including tangible and intangible heritage

- Traditional Owners to speak for Country through their own self-determined processes, including the incorporation of traditional ecological knowledge in NRM planning and delivery.

In developing programs to deliver against these principles, the following priorities have been identified to inform how our actions are planned and implemented:

- Increasing NRM stakeholder awareness of legal requirements for the protection of cultural heritage (intangible and tangible)

- Including Traditional Owners as decision makers in regional planning and investment processes through participation in associated on-Country events, workshops and program/project steering committees

- Respecting the value of traditional knowledge, and the right of its custodians to determine if/how it is shared and used

- Supporting assessments and documentation of cultural values (tangible and intangible), and traditional ecological knowledge and practices

- Supporting the development and implementation of Traditional Owner Country Plans, enabling the application of Cultural Landscape based planning approaches, and delivery against identified cultural objectives

- Enabling the application of traditional knowledge through multiple cultural management practices that provide for healing and strengthening Country and Culture. This includes but is not limited to: reintroducing traditional burning practices; restoring native plant and animal communities; protecting species of cultural importance and returning them to the landscape; applying restorative farming practices; rehabilitating significant cultural sites; expanding traditional languages knowledge and use; and creating educational and interpretive opportunities to share culture.

Priority directions for building Traditional Owner/First Peoples participation in and capacity for NRM, are outlined in Section 3.5 (Community Capacity for NRM). Incorporation of cultural values, objectives, knowledge and practice, as self-determined by Traditional Owners; is also identified as a priority for Biodiversity, Waterways, and Agricultural Land management (Sections 3.1, 3.2 and 3.3).

Strategic directions

Aboriginal Culture and Heritage is intrinsically linked to natural landscapes across the Mallee region and intersects with all other RCS themes. While these themes utilise a prioritisation framework, where the value of the asset x the impact of threatening processes represents a key consideration in targeting delivery, no such analyses of relative value can (or should) be applied to the region’s Culture and Heritage.

Given the finite resources available to the region to support Culture and Heritage focused programs, it is not feasible to expect that every identified action can be applied at a whole-of-region scale over the life of this RCS. To help ensure that effort is directed to actions that will ultimately progress the region’s desired outcomes and vision for Culture and Heritage, four strategic directions have been established to assist in the prioritisation of regional programs. Specifically, that the proposed actions deliver against one of more of the below priorities:

- Awareness of, and compliance with legal requirements for the protection of cultural heritage (intangible and tangible) is increased

- Opportunities for self-determined participation and leadership by Traditional Owners are advanced

- Traditional Owner led practices are rejuvenated and applied to meet cultural objectives that include social, ecological and economic co-benefits

- Application of Cultural Landscapes within regional planning and management frameworks is supported.

This section outlines the medium-term (6-year) and long-term (20-year) outcome targets that regional stakeholders have collectively set for Culture and Heritage management across the Mallee.

Medium-term outcome targets (Table 10) for Aboriginal culture and heritage have been developed to align with, and demonstrate how, the Mallee RCS will contribute to regional indicators (54).

Delivery against these targets will be undertaken as part of the RCS’s integrated catchment management (ICM) – landscape-scale approach to NRM. Detail on the specific management actions and targets to be implemented within individual landscapes, and the local stakeholders that will contribute to their delivery is provided in Section 4 (i.e., Local Areas).

(54) No regional scale baseline information is currently available for two of the three stated medium-term outcome targets (i.e. number of projects that incorporate and deliver on cultural objectives and priorities, and; area subject to Traditional Owner led practices to manage and heal Country). This information gap will be addressed though the RCS MERI Framework, with the establishment and ongoing measurement of associated indicators.