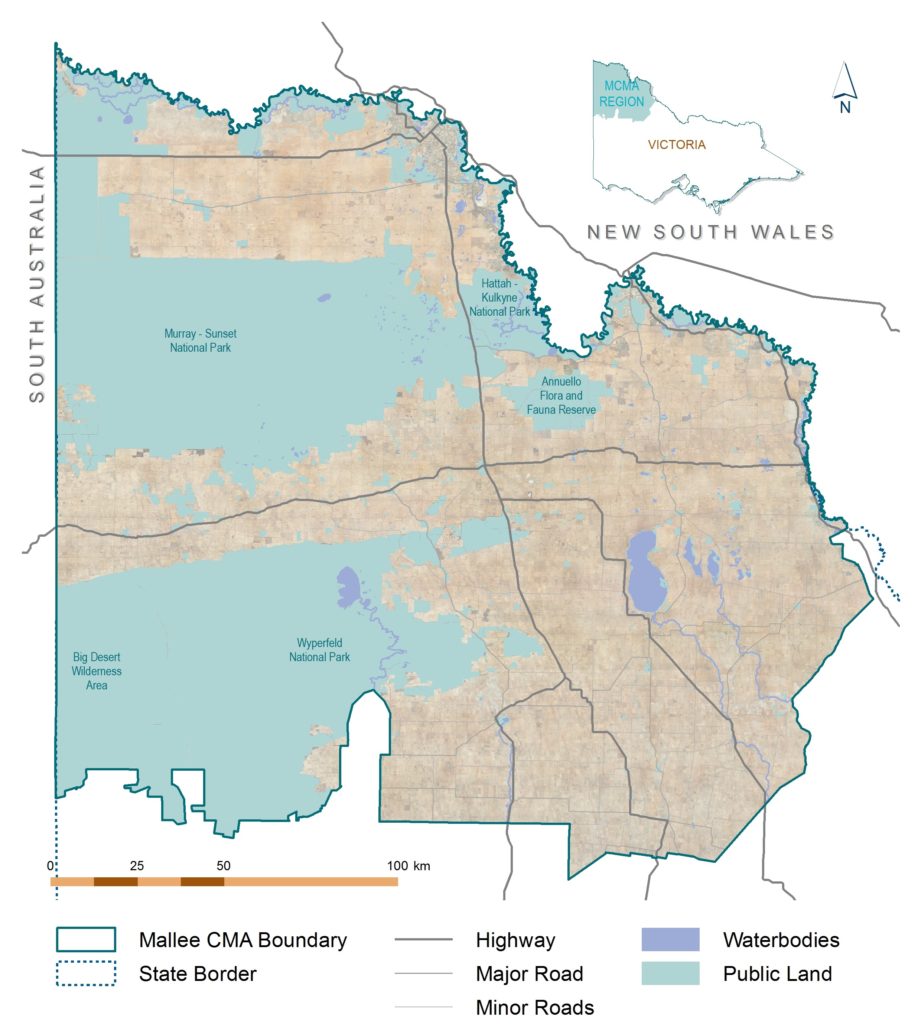

The Mallee region covers 39,939km2, around one-fifth of Victoria. The largest catchment area in the state, it runs along the Murray River from Nyah to the South Australian border and south through vast dryland cropping areas and public reserves (Figure 1).

Figure 1 | The Mallee Region

The Mallee is recognised nationally and internationally for the diversity and uniqueness of its natural, cultural and productive landscapes. Significant features include:

- An extensive network of national parks, state forests and crown reserves including Wyperfeld National Park, Big Desert Wilderness Park, and Big Desert State Forest; which collectively form the largest remnant of uncleared native vegetation in the agricultural areas of south-eastern Australia.

- The Hattah-Kulkyne Lakes – recognised as internationally important under the Ramsar Convention on wetlands.

- Two internationally recognised Important Bird Areas (IBAs) encompassing Murray-Sunset, Hattah-Kulkyne and Wyperfeld National Parks, Big Desert Wilderness Park, and several adjacent state forests and reserves – supporting populations of three globally threatened species: Malleefowl; Black-eared Miner; and Mallee Emu-wren.

- The wetland and floodplain ecosystems of the Hattah-Kulkyne Lakes and Lindsay-Mulcra-Wallpolla Islands – recognised as Icon Sites under The Living Murray Program.

- A key part of Victoria’s food bowl – producing over 30 percent of Victoria’s cereals, and over 90 percent of all grape and nut production.

- A large number of Aboriginal cultural and heritage sites – unique in Victoria both for their concentration and diversity.

The natural character of the region has been shaped by a climate of temperature extremes, low rainfall, and its underlying geology and hydrology; resulting in a series of unique ecosystems and natural features.

The Mallee lies primarily within two broad landform regions: The Riverine Plain, which encompasses the entrenched floodplain of the Murray; and the Mallee Dunefields, a gently undulating plain formed by aeolian (wind) processes. A small area around Birchip lies within the Wimmera Plain.

Native vegetation across the Mallee once covered some 3,919,887 hectares, of which 52 percent is estimated to have been cleared. Much of the region’s remaining vegetation has been reserved in large parks such as Murray-Sunset, Big Desert, Wyperfeld and Hattah-Kulkyne; extensive tracts of riverine and dryland state forests; and over 500 small reserves scattered throughout the agricultural area. Our areas of public land are particularly significant given the largely cleared and fragmented agricultural landscape in which they occur.

Remnants on private land, and the roadsides and rail reserves dissecting this land, represent significant areas of our native vegetation. They are of particular importance for the threatened flora they contain, and for the connectivity opportunities they provide to our region’s fauna.

Extensive water courses and wetlands are a key feature of the region, the Murray River and its environs being one of our most significant areas. North flowing intermittent streams, including Yarriambiack Creek and Tyrrell Creek, and the ephemeral wetland complexes in which they terminate (e.g. Wirrengren Plain, Lake Coorong and Lake Tyrrell) are defining features of the southern part of our region.

There are more than 900 wetlands in the Mallee region, 14 of which are listed as ‘nationally significant’. The Hattah Lakes system is internationally recognised (under the Ramsar Convention) for its value to waterfowl and its importance in maintaining regional biodiversity. The wetland and floodplain ecosystems of the Hattah Lakes and Lindsay-Mulcra-Wallpolla Islands have also been recognised as Icon sites under The Living Murray (TLM) program.

This complex mosaic of vegetation communities and habitats across the Mallee represents significant diversity and includes: Riverine forests and woodlands along the Murray River; the Mallee shrublands and woodlands of the dunefields; the Cypress-Pine, Buloke and Belah woodlands of the lunettes and plains; the woodlands and heathlands of the Big Desert; and the herblands of our ephemeral lakes.

The aquatic and terrestrial habitat provided by these landscapes supports a diverse and unique range of fauna, with many species associated with the more arid interior having their southernmost distribution in the Mallee. Species such as the Red Kangaroo, Giles Planigale, Mallee Ningaui and Mitchell’s Hopping Mouse are not found anywhere else in Victoria; and the Silky Mouse and Western Pygmy Possum are restricted to the Big and Little Deserts.

The Mallee has a particularly rich avifauna, with over 300 bird species having been recorded. The dominant groups, in both numbers and diversity, are the raptors, parrots and cockatoos; and in the Big Desert, the honeyeaters. Large old River Red Gums along the Murray River support many hollow dependent birds like the Regent Parrot. The Pine, Buloke and Belah woodlands support a different suite of hollow-dependent birds such as the Pink Cockatoo. Mallee woodlands and shrublands with Triodia understories support one of the iconic Mallee birds, the Malleefowl.

The number of reptile species in our region exceeds that of anywhere else in Victoria. At least 77 species of reptiles occur including; fresh-water turtles, geckos, legless lizards, dragon lizards, goannas, skinks, blind snakes, venomous snakes, and one python. Inland or more northern species such as the Beaked Gecko and the Coral Snake reach the southern edge of their distribution in the Victorian Mallee. Eleven frog species occur including the Growling Grass Frog and Bibron’s Toadlet.

Nineteen species of native fish have been recorded in the watercourses and wetlands of the region including the Murray Cod and the Murray Hardyhead.

The Mallee has been occupied for thousands of generations by Indigenous people, with human activity at Direl (Lake Tyrrell) dated as far back as between 26,600 and 32,000 years ago; although use of the area possibly began as early as 45,000 years ago (1).

The region’s rich and diverse Aboriginal heritage has been formed through the historical and spiritual significance of sites associated with this habitation, together with the enduring connection Traditional Owners/First Peoples have with the Mallee’s natural landscapes.

The first inhabitants of our region were numerous Aboriginal tribes of different language groups, including Ngintait, Ngarkat, Latji Latji, Nyeri Nyeri, Wergaia, Wadi Wadi, Wemba Wamba, Jari Jari, and Tati Tati. Given the semi-arid climate of the region, ready access to more permanent water has been a major determinant of human habitation, and as such the highest density of identified Aboriginal cultural heritage sites are located around or close to areas of freshwater sources.

The high number of cultural sites throughout the Murray floodplain is unique in Victoria, both for their concentration and diversity and include large numbers of burials, middens and hearth sites. In the south of the region, freshwater lakes, streams and wetlands were focal points for the region’s Traditional Owners. Many lakes were the sites of large gatherings of several family groups that afforded trade and cultural exchanges. Intangible cultural heritage is integral to these landscapes, including the traditional knowledge, practice and expressions (e.g. biocultural knowledge, ceremonies, language, stories) passed down from generation to generation.

Introductions provided by several of the region’s Traditional Owner groups provide further context regarding their connections to Country and aspirations for these landscapes (see Acknowledging Country Section).

(1) Richards et al. (2007), Box Gully: new evidence for Aboriginal occupation of Australia south of the Murray River prior to the last glacial maximum, Archeology in Oceania 42 1-11.

Despite the semi-arid nature of the region, the predominance of winter rainfall and access to reliable water from the Murray River has allowed the Mallee to develop into an agriculturally diverse region; with important irrigation areas in the north along the Murray, and extensive dryland cropping and grazing areas in the south, east and west. In total, some 62 percent of the region’s area is given over to agricultural production.

The productive capacity of our agricultural lands has risen steadily over the last half of the 20th century in response to increased mechanisation, improved management techniques, and genetic improvement of crops. Today, agriculture remains our major land use and most economically important industry.

Dryland farming in the region covers some 2.4 million hectares and includes the cropping of a wide variety of cereals, pulses and oilseed crops such as wheat, barley, vetch, lupins, chickpeas and canola.

Livestock also forms a part of many farm operations and primarily includes sheep for their wool products and lambs for their quality meat. Cattle and goats are also present in smaller numbers. There has however been an overall decline in livestock numbers over the past decade as a larger proportion of farmers operate more intensive no-till or reduced till cropping systems, with a share of these no longer running livestock at all.

Irrigation in the Mallee extends adjacent to the Murray River corridor from Nyah to the South Australian Border; encompassing Private Diverters and the Pumped Irrigation Districts of Mildura, Merbein, Red Cliffs, Robinvale and Nyah. A 191,600 hectare groundwater management area centred on the town of Murrayville also exists.

The major irrigated sectors are almonds, table and wine grapes, and citrus. Between 1997 and 2021, irrigation development reliant on water from the Murray River has increased from 39,470 hectares to 81,355 hectares, representing a more than doubling of the irrigable area. The industry has seen increased diversity in crop types and is becoming far more dynamic in response to climatic conditions and market forces. Almonds have become the single largest crop by area and water demand.