Ongoing pressures from a range of long-term and emerging threat processes directly influence the condition of our natural, cultural and productive landscapes. Regional efforts to manage these processes is vital to securing the environmental, economic, cultural and social values these landscapes provide.

The Mallee currently faces several challenges that may compromise both the effectiveness of our management actions and the resilience of our landscapes. Conversely, there are also opportunities for improvement in how we plan for and deliver NRM.

Collectively, these threat processes, challenges and opportunities represent key drivers which have the potential to significantly influence outcomes achieved through this RCS and beyond. How we respond to these drivers will play a critical role in shaping the future condition of our region.

1.4.1 Challenges and opportunities

The condition of our natural, cultural and productive landscapes can vary significantly with seasonal conditions and events in the Mallee, where some annual climate variability is the norm, particularly in rainfall. Over recent years it has become increasingly apparent that long-term climate trends are influencing the biophysical values these landscapes support, and the services they provide.

Climate variability

The variability of our climate presents significant external risks to NRM in the Mallee. Weather extremes such as drought, flood, heavy frosts, hail, heat waves and high winds are not uncommon and can have severe impacts on the region. These extremes have the potential to either directly impact the region’s management actions, or impact indirectly by generating damaging events such as fire or dust storms.

They can also influence the short-term capacity of individuals and organisations to be involved in management interventions on land that they manage by damaging infrastructure, or otherwise diverting financial or physical resources in order to respond to such events.

In many cases, these weather events pose short-term interruptions over a generally localised area. While they are significant and often traumatic to those directly affected, their impact does not usually extend across the entire region. Under these circumstances it is important that our NRM stakeholders have the flexibility to revise and adjust their programs without significant difficulty.

Drought is however an exception in terms of extreme weather as it typically impacts across large swathes of the landscape. Under these conditions it is important that there is a range of management responses available to our NRM stakeholders that can benefit both the landscape and our communities.

Climate change

A changing climate has been identified as a critical issue facing the Mallee, with many impacts predicted under various greenhouse gas emission scenarios already being experienced. Key examples of changes that have occurred over the past 30 years in the Mallee include (8):

- Annual rainfall has decreased by around seven percent, mostly in the autumn and spring months

- Dry years (lowest 30%) have occurred 13 times, and wet years (top 30%) have occurred six times

- Spring frosts have been more common and have been occurring later in the season

- More hot days, with more consecutive days above 38°C.

Climate change projections produced for the Mallee by CSIRO (9) identify that these trends are expected to continue, with:

- Maximum and minimum daily temperatures continuing to increase over this century (very high confidence)

- Rainfall continuing to be very variable over time, but over the long term it is expected to continue to decline in winter and spring (medium to high confidence), and autumn (low to medium confidence), but with some chance of little change

- Extreme rainfall events are becoming more intense on average through the century (high confidence) but remaining variable in space and time

- The number and risk (i.e. Forest Fire Danger Index) of fire days increasing (high confidence).

Based on these future climate scenarios, it is projected by the 2050s, the climate of Mildura could be more like the current climate of Menindee, and Swan Hill more like Balranald.

These changes have potentially profound implications for our natural landscapes. Biophysical systems are inherently sensitive to changes in both weather and climate. This sensitivity allows for these systems to ‘react’ in a timely fashion to these changes using whatever adaptive strategies that are available to them. With predictions for increasing temperatures and a shift in rainfall seasonality, it is expected there may be a substantial change in ecological landscapes across the Mallee.

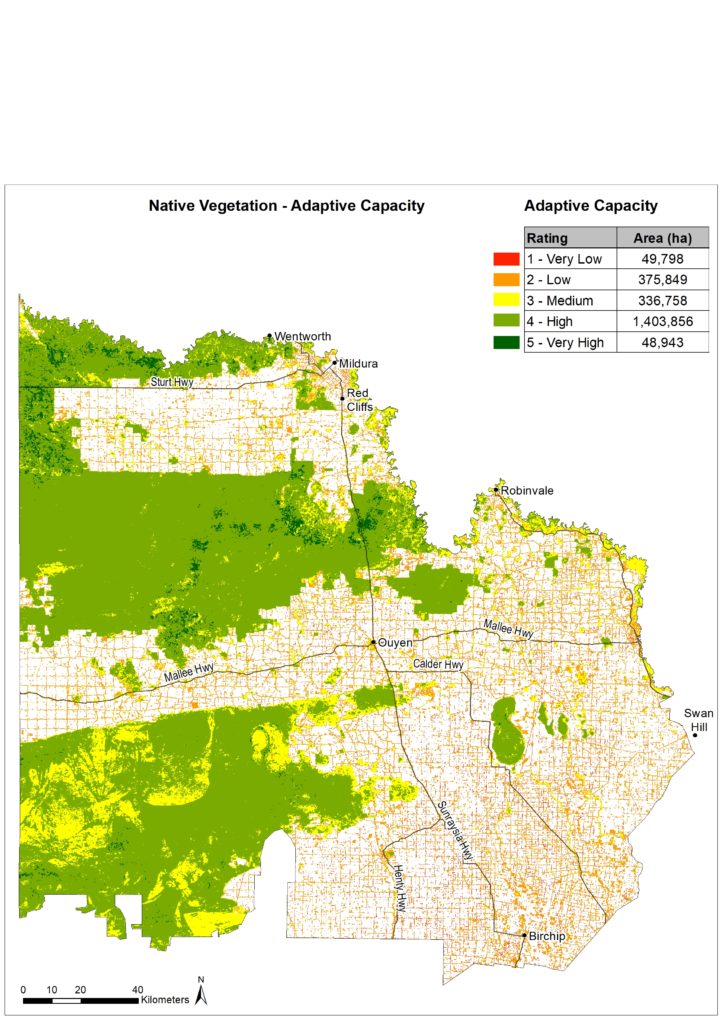

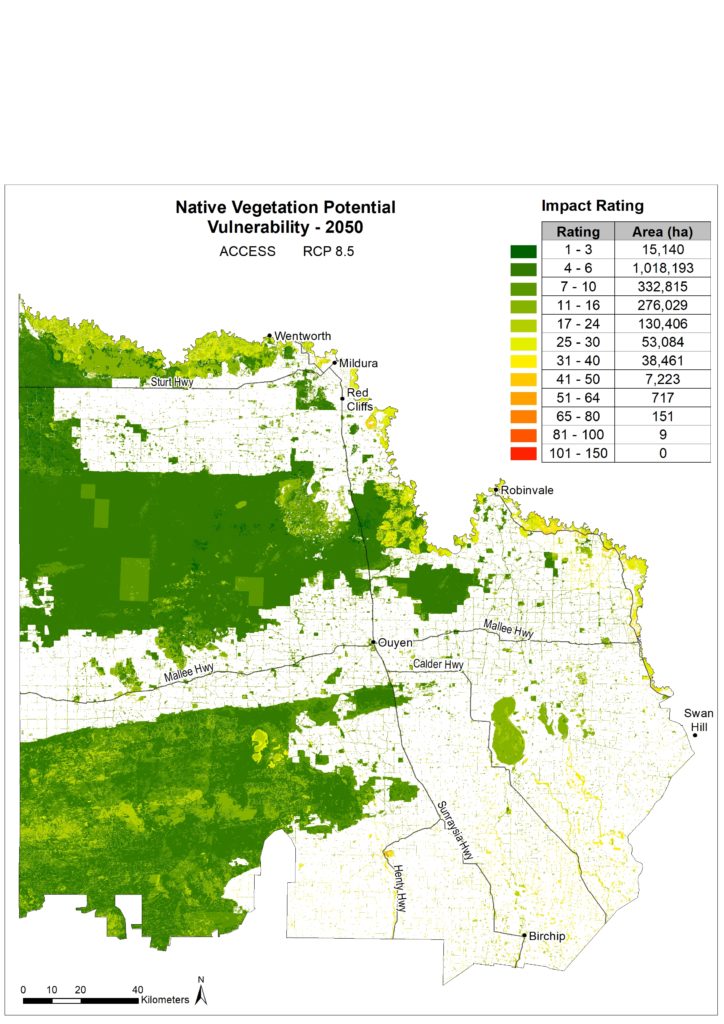

The capacity of our current biophysical assets to adapt in the face of such change is complicated by the modern, fragmented landscape within which they exist, with connectivity and scale directly influencing both the adaptive capacity and vulnerability of native vegetation (Figure 3).

Changed climate conditions are likely to contribute to significant change in the current biodiversity of the Mallee by exacerbating the negative impacts of existing threats such as habitat loss and fragmentation, invasive species, and broad scale bushfires. It has been suggested that under a changing climate, ecological conditions for plant communities in the Mallee (particularly those in the north and east) may be substantially changed by as much as 70 percent (10).

Decreases in rainfall and higher evaporation rates will mean less soil moisture and consequently, less water for rivers and wetlands. Demand for water may also increase as a result of warmer temperatures and population growth. Therefore, our need to use water more efficiently will be even greater.

Lower flows and higher temperatures may also reduce water quality within the catchment and create a more favourable environment for potentially harmful algal blooms. These blooms contribute to fish deaths in waterways, but also pose significant economic costs. Drinking water has to be specially treated, regional tourism is often affected, and water for livestock has to be sourced elsewhere.

(8) Bureau of Meteorology and the CSIRO (2019): Regional Weather and Climate Guide – Mallee, Victoria.

(9) Clarke et al. 2019. Mallee Climate Projections 2019. CSIRO, Melbourne Australia

(10) Harwood, et al. (2014). 9-second gridded continental Australia potential degree of ecological change for Vascular Plants

Figure 3A | Adaptive capacity of native vegetation in the Mallee Region (adapted from Spatial Vision 2014).

Figure 3B | Potential vulnerability of native vegetation in the Mallee Region (adapted from Spatial Vision 2014).

Climate change will potentially impact the types of crops we grow and the productivity of our agricultural systems. Any reduction in rainfall will place most farms under stress, particularly when linked to higher temperatures. Changes that will directly influence land use and management decisions in both dryland and irrigated agriculture, as farmers seek to counter new climate outcomes and maintain farm income.

Recent research estimates that by 2070, without adaptation, crop yields could be reduced by up to 30 percent for almond and citrus plantings, and 35 percent for some grape varieties. Strategies such as crop modelling, breeding and selection will be essential across all industries to help mitigate these impacts (11).

The overall impacts of climate change on our communities are wide-ranging and complex. To adapt to changing conditions, our community needs to be resilient in the face of stresses and shocks. This will be key to both livelihood adaptation and the ability of the community to effectively manage the natural resource base for environmental, cultural, social and economic outcomes.

Despite the significance of climate change as a risk to the Mallee, we do have the opportunity to plan for these expected changes by identifying and implementing climate-ready adaptation options that influence land management decisions, provide habitat restoration for biodiversity migration, and improve knowledge to generate greater capacity for individuals and stakeholders to respond over time to pressures arising from a changing climate.

An example of climate-ready approaches currently being applied in the region is revegetation works that plant a variety of species sourced from both the local area, and from additional locations with a similar climate to that predicted to occur at the planting site in the future. By incorporating material with both local and climate-adjusted provenance, the aim is to increase genetic diversity, and ultimately climate adaptability, of the vegetation.

Carbon Markets

There are likely to be a number of ways in which our land managers can participate in emerging carbon market opportunities. This includes the sequestering of carbon through activities such as revegetation and land management practices (e.g. maintaining groundcover), and potentially the restoration of ‘blue’ carbon within waterway ecosystems.

In planning for and participating in these markets, it is essential the impacts (both positive and negative) of associated activities on our natural, productive and cultural landscapes are fully recognised.

Carbon markets that support bio-sequestration can also deliver a range of co-benefits for biodiversity. Incorporating activities such as biodiverse carbon plantings using vegetation communities specific to the location prior to clearing (i.e. rather than isolated monocultures), and native vegetation retention and protection on-farm, have the potential to increase habitat extent, connectivity and restoration outcomes on both public and private land. Conversely, both biodiverse and non-biodiverse (single species) plantings may impact negatively on water availability and agricultural production.

Ongoing collaboration between government partners, land managers and investors is required to maximise the potential biodiversity co-benefits that carbon focused projects can deliver.

Renewable Energy

The Victorian Government is developing Renewable Energy Zones (REZs), with the aim of strengthening the states transmission network to support development of large-scale renewable energy generation projects. There are six REZs planned for Victoria, with proximity to existing transmission lines and the availability of renewable energy resources key considerations in their selection. One of these zones, the ‘Murray River’ REZ, is located in the Mallee.

Currently in early stages of development, the REZ’s are seeking to identify community values and areas of environmental and economic significance through consultation with local residents, Traditional Owners, industry and land managers. On the basis that the next generation of renewable energy projects would present the region with key economic development opportunities, it is important that regional NRM stakeholders participate in these processes to ensure that any impacts on our natural, cultural and productive landscapes are also considered.

(11) Implications of climate change for horticulture in the Victorian Mallee: 2021 report for Mallee CMA and Agriculture Victoria.

Fires are a dominant part of the Mallee landscape and are a major factor in determining the nature and distribution of our flora. Responses to fire by our vegetation communities vary widely; with many species dependent upon it for regeneration, and others with no adaptation to it at all.

Changes in fire frequency, intensity, and extent since European settlement has altered vegetation structure, and influences the mosaic of differently aged, post-fire vegetation communities across the landscape. The management of fire for ecological purposes is complex given that different fauna species require differently aged vegetation to meet shelter, food and breeding requirements; and that the ideal fire regime for many of our species is still largely unknown.

A key challenge for the region is to realise fire management objectives of protecting people and property, while meeting the ecological needs of our natural landscapes.

The Loddon Mallee Bushfire Strategy (2020) sets out the region’s approach to reduce bushfire risk and maintain ecosystem health (i.e. fuel management, targeted community engagement, prevention of human-caused ignition, and first-attack suppression). This strategy informs development of the Loddon Mallee Joint Fuel Management Plan, a rolling three-year program of fuel management works on public and private lands carried out by Forest Fire Management Victoria (FFMVic) and Country Fire Authority (CFA).

Engagement processes employed by these strategic and operation planning processes provides for specialist, Traditional Owner and local community input; the identification of key information gaps, and enhanced partnerships; all of which are integral to continuous improvements in managing fire for environmental gains.

Regional planning processes also recognise the role of cultural burning in the landscape, with Traditional Owners nominating areas of cultural burns as part of the 3-year fuel management program.

Assessments of water supply and demand from perennial horticulture in the southern Murray-Darling Basin have identified increasing challenges for plantings in the lower Murray region to meet their water needs in dry years, and that any new plantings could exacerbate water supply risks. If irrigated horticulture continues to expand without associated reductions in water demand (i.e. adaptive management, industry restructuring), there will be increased risk to supply for existing businesses and increased competition in the water market. Irrigator understanding of the limits to water availability, and therefore the limits to expansion, and how they will be enforced will be central to facilitating change. The impact of climate change (e.g. increased risk/intensity of drought) on water allocations under climate change also requires ongoing consideration.

Changes in demand and supply have also increased the challenges of delivering water to where and when it is needed. Continued expansion of horticultural plantings in the Mallee regions of the Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia, has concentrated irrigation demand and shifted water use further away from major dams. Given that it takes three weeks to deliver water from the Hume Dam to Sunraysia, the challenge of providing peak demand (e.g. during heatwaves) is likely to become more difficult if peak irrigation continues to increase as existing plantings mature and new permanent planting are established across the tri-state Mallee regions.

A challenge that will be further exacerbated under a changing climate where the frequency and duration of hot days are projected to increase.

Small rural communities in the Mallee continue to experience population decline and increasingly older age profiles. This reflects the continuing trend for young people to leave rural areas and relocate to larger population centres (e.g. Mildura) to access a greater availability of employment, education, and training opportunities. In some areas, these population changes also coincide with a decline in key industries and the withdrawal of services, both public (e.g. schools and hospitals) and private (e.g. banking and retail), making living in these areas less desirable and further impacting on the wellbeing and sustainability of the remaining community.

The growth of our urban areas at the expense of our rural population presents a great challenge in sourcing the necessary co-investment of time and resources from a diminishing (and ageing) population of rural landholders and community-based NRM groups.

There is a risk that there will be insufficient people on the ground in large parts of our region to help implement the interventions that will protect and enhance our assets and the services they provide. Within this context it is essential that the capacity of our rural communities is recognised and that adequate support mechanisms are established where necessary. Opportunities for innovative and more efficient delivery mechanisms should also be encouraged.

Increased application of existing and emerging technology has the potential to enhance both the effectiveness and efficiency of NRM in the Mallee. The Victorian Government’s strategy for agriculture, for example, identifies modernisation as a core theme for agriculture to thrive over the next decade; estimating 80 percent of improvements in Australia’s broadacre productivity since the late 1970s has come from technology, and that full application of digital agriculture could lift production by a further 25 percent (12).

Overall advances in satellite, and other remote sensing technologies is vastly increasing the data available to support NRM decision making. Digital technologies such as drones, weather stations, soil moisture probes and sensors can support improved planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation process. Applying technology to develop innovative engagement and communication approaches can also assist in overcoming participation barriers often identified by our rural communities (i.e. distance and time).

Digital connectivity and literacy can however impact the uptake of such technology. Connectivity varies significantly across the region, with many ‘black spots’ across more remote areas. Only 60 percent of households in the Mallee report having internet access; 10 percent below the State average (13).

Enhanced connectivity, together with increased awareness of the efficiencies that new technologies can provide will be important factors in influencing increased application across the Mallee.

(12) Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions (2020): Strong, Innovative, Sustainable – A new strategy for agriculture in Victoria.

(13) Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016. Census of Population and Housing, Type of Internet Connection. http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/Data

The region’s natural landscapes are fundamental to Country and the cultural identity of Traditional Owners. Caring for and healing Country with traditional ecological knowledge and customs built over thousands of years of practice is integral to this connection.

By valuing and supporting Traditional Owner leadership and expertise, we can more effectively care for and heal Country with traditional ecological knowledge and customs; providing for ongoing ecological benefits and enhanced connections with Country.

The guiding principle for Traditional Owner participation and leadership is self-determination. This is described in DELWP’s Pupangarli Marnmarnepu ‘Owning Our Future’ Aboriginal Self-Determination Reform Strategy 2020–2025, which aligns with whole-of-government commitments set out in the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework (VAAF), and the VAAF Self-Determination Reform Framework, which guides government and agencies to enable action towards Aboriginal self- determination. From an NRM perspective, this means empowering Traditional Owners to participate and lead, if and how they choose, efforts to manage and heal Country.

Prior to colonisation, Mallee landscapes were healthy and provided sustenance for the people and wildlife that lived here. With European settlement came foreign plants, animals, and changed management practices which impacted the land and the people. First Nations people were forced out of the landscape and could not maintain their obligations to Country. The First Peoples Assembly of Victoria and the Victorian Government have made a shared commitment to truth telling through the Yoo-rrook Justice Commission. The Commission is expected to establish an official record of the impact of colonisation on First Peoples in Victoria and make recommendations about practical actions and reforms needed. This will likely inform catchment management across the State and the Mallee region into the future.

The State of Victoria is also working with Aboriginal Victorians through the First Peoples Assembly to progress discussions on Treaty. Treaty is an agreement between governments and First Nations – it is an opportunity to recognise and celebrate the status, rights, cultures and histories of Aboriginal Victorians. It also helps address the wrongs to build stronger relationships between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Victorians, and the State.

Connections to nature are important for the well-being and social fabric of our communities. Recreational and amenity values provided by our natural landscapes are appreciated by both locals and visitors alike; supporting a suite of activities such as camping, walking, swimming, fishing, bird watching, boating, four wheel driving, and community events.

Recreational sites can also provide opportunities for tourism and hospitality, attracting visitors from within and outside of the region. In small towns, features such as a waterway can provide for important social connections and income for local businesses.

Integrating the recognition and inclusion of these values into regional NRM planning and delivery processes allows for their ongoing protection and enhancement. This includes considering the impact (both positive and negative) of environmental focused management actions on sites with recognised, or potential, recreational and aesthetic values; and improving associated infrastructure to enhance accessibility and amenity.

A 2020 review of the EPBC Act found that to deliver the broad restoration required to address past loss, build resilience, and adjust the environmental trajectory from its current path of decline, greater collaboration is needed between governments and the private sector to invest in the environment (14). Victoria’s Biodiversity Strategy (Protecting Victoria’s Environment – Biodiversity 2037) also recognises that the protection and restoration of biodiversity requires secure and sustained investment over the long term from a variety of funding sources, including the private and philanthropic sectors.

With the level of investment provided through ‘traditional’ government based funding models unlikely to support delivery against all of the objectives of this RCS and increased interest from the corporate sector to demonstrate social licence and green credentials; it is important that regional partners explore opportunities to attract diverse funding mechanism and potential co-funding/leveraging arrangements.

(14) Australian Government Threatened Species Strategy (2021-2031).

1.4.2 Major Threats

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation

The extensive clearing of Mallee vegetation for agricultural production has resulted in a mosaic of scattered, often small and isolated patches of remnant vegetation dispersed across the landscape. While much of the pattern of the Mallee landscape was set many decades ago, there has been an ongoing loss of small vegetation patches which continues to add to this fragmentation threat.

This loss and fragmentation of native vegetation makes much of our biodiversity vulnerable to a range of threatening processes. Without effective connectivity and access to regenerative material, many fragmented and isolated habitats lack the necessary resilience to respond successfully to both ongoing and emerging threats.

Clearing vegetation around waterways and within their catchments has significantly changed the amount, quality and flow pattern of run-off entering waterways. Run-off from highly modified catchments is likely to contain high levels of sediment and nutrients, pollutants, and seeds of exotic plants.

Vegetation fragmentation decreases both the habitat value of individual patches for many fauna species and their ability to move through the landscape. Lack of connectivity is a major factor in the decline of many now threatened species in the Mallee.

Added to this is the challenge of under-representation. While large contiguous blocks of terrestrial habitat that remain in the Mallee are protected through the formal reserve system, they do not represent the entire diversity of the region’s original habitat and associated ecosystems. A key example is the Buloke Woodland Community which was extensively cleared for agriculture and is now considered endangered at a national scale.

Altered Hydrological Regimes

Flow modification of the Murray River system has occurred to meet the needs of navigation, irrigation and urban water use. River regulation modifications include less variation in channel flows, a reduction in the frequency and duration of small and medium floods, weirs which raise water levels immediately upstream and redirection of flows into some anabranches to supply irrigators.

This has altered the wetting and drying phases of many wetlands and ephemeral anabranches, by either permanently inundating the area, or by restricting flows. Changes which can ultimately have a significant impact on important riparian habitat and associated vegetation communities (e.g. River Red Gum, Black Box), fish populations, nutrient cycling, water quality, and channel/wetland shape and form.

The Avoca system, containing Lalbert and Tyrrell Creeks, is one of the least regulated rivers in Victoria. The construction of levees to restrict flooding of adjacent land and other management activities such as clearing, cultivation and the application of gypsum have however changed run-off patterns across the landscape. Additionally, the construction of catchment dams in the upper Avoca has reduced inflows into the creeks.

By contrast, the Wimmera River is heavily regulated and its two distributaries occurring in the Mallee, Yarriambiack and Outlet Creeks together with their associated wetlands, are largely influenced by headwater storage.

In terms of the region’s off-stream wetlands, their natural run-off patterns have been significantly affected by land management (e.g. clearing and cultivation). While many of these wetlands were fed by a domestic channel to support water storage functions, following pipeline establishment they now rely on connections to receive water allocations.

Water Quality

Irrigation development can change saline groundwater flow patterns, increasing salt inputs to the floodplain and associated waterways. River salinity can increase even during high rivers and particularly on flood accessions when accumulated salt drains to the river.

This drainage of water from irrigation into low lying areas of frontage, the river, or the adjoining floodplain led to rising water tables and salinity, waterlogging and increased nutrients to waterways. This can increase the risk of algal blooms, lead to the decline or even death of native vegetation, and can impact the amenity of the affected site. Poor structural conditions of drains may also result in erosion, increasing sediment loads to waterways.

Failed or failing groundwater bores also present a threat to water quality within the Murrayville Groundwater Management Area (GMA), particularly where the Murray Group Limestone aquifer is overlain by the saline Parilla sands aquifer. The older stock and domestic bores drilled into the limestone aquifer are likely to deteriorate as the steel casing corrodes, allowing water from the saline aquifer above to enter the fresher limestone aquifer and cause contamination.

Proper capping and decommissioning of old bores is important to protect the water quality of the Murray Group Limestone Aquifer. This also applies to the numerous bores drilled over many years for monitoring and investigative purposes outside of the Murrayville GMA.

It is also possible that pumping for irrigation within the Murrayville GMA may increase the rate of naturally occurring lateral movement of saline groundwater from the east. Monitoring has not provided any evidence of this to date.

Soil Health Decline

While the Mallee contains significant areas of naturally saline surfaces, it is estimated that some 55,000 hectares of land has become salinised since European settlement (15). This induced or secondary salinity has occurred as a direct consequence of changed land use and management (i.e. the removal of deep rooted perennial vegetation for more shallow rooted, annual crops and pastures) which has unbalanced natural water table levels, causing a rise in saline water tables. Once water tables rise to within about two metres of the soil surface, groundwater is drawn up by capillary action, leading to salt accumulation and salt scalds.

These changes to soil chemistry can pose a significant threat to natural, cultural and productive landscapes. In some areas where salt levels are extremely high, no plant species can grow and ecosystem function is lost. In other areas, salt tolerant species have expanded significantly, replacing the original habitat.

Although the spread of dryland salinity is considered to have slowed or receded under extended dry periods, the threat is likely to increase if there is a return to wetter conditions, particularly an increase in episodic high intensity rainfall events over summer.

Seeps resulting from localised, perched water tables have however rapidly increased over the last decade due to a combination of landscape, seasonal and farming system factors; leading to the waterlogging, scalding and salinisation of productive cropping ground in swales, a reduction in paddock efficiencies, and increased machinery risks (16).

Mallee agricultural soils are highly susceptible to wind erosion given their light structure, with the likelihood of erosion strongly linked to land management (e.g. groundcover) and climatic conditions (e.g. wind strength). Wind erosion processes can have a significant impact on production, including; loss of soil fertility, sand blasting of emerging crops, and localised ‘blowouts’. Adverse effects off site extend to harmful airborne dust pollutants, reduced visibility, infrastructure inundation, and increased sediment and nutrient loads in waterways.

Sand drift can also inundate infrastructure and expose cultural sites, smother the ground layer of native vegetation, and threaten regeneration of the shrub layer and over-storey. Drift also destroys the habitat of ground dwelling fauna. The impact of erosion on vegetation remnants is greatest on the western and southern perimeters, where the smaller the remnant, the greater the edge effect. This impact is dramatic on the western and southern flanks of roadsides most noticeably where they intersect dunes.

While widespread changes in dryland management practices are supporting increased groundcover and overall soil stability, there is still a need for further improvement. The dust concentrations generated under current land practices across the Mallee impact both remote and urban areas through loss of air quality, clean-up costs and interruption to economic activity (e.g. health impacts, closed building sites and airports). Wind erosion is also continuing to threaten the long-term viability of many agricultural businesses, and directly impacting the condition of native habitat.

Soil organic carbon (SOC), as the measurable component of soil organic matter, is critical to the physical, chemical and biological function of agricultural soils. SOC levels vary considerably (generally between 0.2 and 1.5 percent) across the region and are inherently linked to soil texture, which shifts from sandy loam in the north to clay loam/clay soils in the south.

Research indicates that carbon stocks in the Mallee may still be in a state of decline from initial clearing and cultivation of the native soil, and that further shifts in management practices are required to arrest this decline. In determining where and which management practices can potentially increase carbon stocks, two core factors have been identified: productivity needs to be maintained at a high level, relative to potential, to optimise biomass production and ensure that carbon capture by the plant flows through to the soil; and any chemical, physical or biological soil constraints need to be overcome to maximise water-use efficiency (17).

(15) Grinter, V., & Mock, I. (2009). Mapping the Mallee’s Saline Land . Report for the Mallee Catchment Management Authority.

(16) McDonough, C (2020) Soaks are seeping across the Mallee – what can be done about it?

(17) McKenzie, N., & et. al. (2017). Priorities for improving soil condition across Australia’s agricultural landscapes. Report prepared for the Australian Government Department of Agriculture and Water Resources. Canberra: CSIRO.

Large-scale bushfires represent a key threat to Mallee biodiversity by reducing existing populations of native species, reducing resources available to those remaining species, and exacerbating the risk of existing threats (e.g. increased predation and grazing pressure). An increase in fire weather days under a changing climate has the potential to increase the frequency and intensity of large-scale bushfires across the region, further adding to management complexities.

Grazing Pressure

Grazing and browsing by livestock, rabbits, feral goats, overabundant wildlife (i.e. kangaroos), feral pigs and, to a lesser extent deer, influences vegetation health by reducing floristic diversity and altering structure. This reduces resilience to shocks (e.g. drought, fire), and ultimately the ability to function as effective habitat.

Grazing by livestock can cause significant damage to the ecology of native vegetation, particularly within small remnant patches on private land where damage is most prevalent today. Within riparian areas, livestock grazing can lead to increased bank erosion as well as increased run-off of sediment and nutrients to the waterway.

European rabbits represent a key risk to the condition of both smaller remnants and large reserves. Impacts from rabbits can be very selective and have a significant effect on regeneration processes within the region’s Semi-arid Woodlands, including threatened Pine, Buloke and Belah communities. Overabundant kangaroo populations compound this grazing pressure, particularly where vegetation recovery is occurring, by; reducing grass cover, understory species diversity, and seedling survival.

Feral goats are predominantly browsers and less dependent on the herbaceous groundcover than rabbits and kangaroos, directly impacting seedlings and young saplings, and compromising regeneration of the shrub and canopy layers.

Feral pigs are opportunistic omnivores, and their diet varies according to the seasonal availability of resources. While they show a preference for succulent green vegetation, they will also eat foliage, stems, rhizomes, bulbs; and a wide range of animal material (e.g. invertebrates, fish, frogs, reptiles, birds and small mammals). They primarily impact riparian habitat through their grazing, trampling, rooting and wallowing activities.

Rabbits, feral goats and feral pigs also cause damage to Cultural Heritage sites through their burrowing, trampling and wallowing habits.

Introduced Predators

Across Australia, it is estimated that foxes and cats combined are killing more than 2.6 billion mammals, birds, and reptiles every year, putting immense pressure on the survival of many native species (18). The introduced red fox and feral cat played a large part in the extinction of at least 34 mammal species at a national scale, and continue to be implicated in the ongoing decline of many threatened fauna species (19).

Foxes and feral cats are widespread across the Mallee and represent an ongoing threat to the persistence of native fauna species, further reducing the abundance and distribution of many threatened populations; with ground foraging and ground nesting species at particular risk.

Introduced Fish Species

European Carp are a major threat to the ecology of the Murray River, its tributaries, and associated waterways. Carp can impact waterways by undermining banks, destroying aquatic vegetation, and increasing turbidity which affects water quality. Carp together with Gambusia also compete with native fish for food and habitat, and prey upon the eggs and juveniles of other fish species.

Environmental Weed Competition

Environmental weeds can outcompete native species for space, light, nutrients and water; impeding regeneration processes. They reduce the diversity of native species within a vegetation community, changing its composition and structure. They can also impact on the use of popular recreational areas, affecting aesthetic values and limiting access.

Of particular concern are those weeds that have the capacity to change the character, condition, form or nature of ecosystems over substantial areas.

In some instances, weed proliferation may impact on water quality as a result of nutrient pulses caused by rapid shedding of leaves (e.g. willows). An ability to spread rapidly can also result in physical interruptions to water flow causing changes in water course behaviour.

Key terrestrial weeds currently impacting Mallee habitat include: African Boxthorn, Bridal Creeper, Prickly Pear and Wheel Cactus, Noogoora Burr, Willows, Spiny Rush, Wards Weed, and exotic perennial grasses such as Buffel Grass. A new emerging weed in the Mallee, Buffel Grass is considered one of Australia’s worst environmental weeds with the potential to transform large areas of native habitat if not adequately contained. Leafy Elodea, Arrowhead and Cabomba are key aquatic weeds threatening our waterways.

Overall risks posed by environmental weed infestations are expected to increase as a changing climate provides new opportunities for existing weed species by altering ecological niches, and aids the establishment of new species.

Agricultural Pests and Diseases

The weeds, pest and disease spectrum impacting dryland and irrigated agriculture is continually evolving with crop diversification and changes in management practice. Pest animals, insect incursions, plant diseases caused by nematodes, fungal, bacterial and viral causal agents, and weed competition, including herbicide resistant population, all add to the complexity, cost and risk of modern-day agriculture.

With these risks expected to increase as a range of new species (especially weeds) and the invasiveness of current species adapt to a changing climate, ongoing biosecurity and management is essential to minimising productivity losses. Plant genetics, biological controls and new technologies are also key components of the multipronged and collaborative approaches required to protect agricultural industries.

(18) Stobo-Wilson et al. Counting the bodies: Estimating the numbers and spatial variation of Australian reptiles, birds and mammals killed by two invasive mesopredators. Diversity and Distributions Journal, March 2022.

(19) National Environmental Science Programme, Threatened Species Recovery Hub (2021).

Mallee waterways, parks and reserves are popular recreational destinations for the local community and visitors from outside the region, making recreational use an important social value of these sites. However, the environmental impacts of this use also make it a key threat. The impacts of recreation can include littering and rubbish dumping, track proliferation, soil compaction and erosion, firewood collection, vandalism, and illegal hunting. As population and visitation increase, so do the potential impacts on natural and cultural values.

The decline in vegetation cover and habitat complexity within remnant native vegetation can constrain or prevent regeneration, leading to loss of habitat in the longer term. While many of the threat processes detailed above are primary contributors to this process (e.g. fragmentation, grazing pressure), efforts to restore impacted habitat through revegetation must also consider the impact of a changing climate on species selection. Specifically, in terms of their genetic appropriateness for maintaining capacity in the current and future ecological landscape.

Community opinions, approaches and values can run counter to the messages and knowledge about NRM, threatening the success of the wider communities’ efforts to enhance their natural, cultural and productive landscapes. Such perceptions include ‘right of unfettered access’ that results in the removal of traffic management infrastructure; and ‘we are doing no harm’ where individuals are not aware of the cumulative and incremental impact of actions such as off-track access and firewood collection.