Vision

Biodiversity is healthy, resilient and valued

Scope

Populations of threatened or significant species; occurrences of threatened ecological communities (aquatic and terrestrial species/communities). Terrestrial habitat provided by ecological vegetation classes and their contribution to landscape processes#.

#Populations of threatened or significant species; occurrences of threatened ecological communities, and: Terrestrial habitat provided by ecological vegetation classes and their contribution to landscape processes

The Mallee supports a diverse and unique array of native flora and fauna, several of which occur nowhere else in Victoria and many others at the edge of their range (e.g. representing the southernmost distribution), yet genetically distinct from their northern or southern relatives. This includes a greater diversity of reptiles than any other region in Victoria.

For the purpose of the RCS, this biodiversity theme considers those species and communities which are listed as threatened at either a federal or state level (i.e. under the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) and/or the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (FFG Act). Of particular note are our non-eucalypt woodlands which contain significant remnants of an EPBC listed ecological vegetation community (Buloke Woodlands of the Murray-Darling Basin Depression Bioregion) and five communities listed under the FFG Act (e.g. Semi-arid Herbaceous Pine Woodland Community).

The region also provides critical habitat for the EPBC and FFG listed Mallee Bird Community which comprises 20 bird taxa (20); six of which are also individually listed as threatened at both a federal and state level (i.e. Black- eared Miner, Mallee Emu-wren (Figure 14), Malleefowl, Red-lored Whistler, Mallee Western Whipbird, and Regent Parrot).

The FFG listed Lowland Riverine Fish Community of the Southern Mallee Darling Basin is dependent on regional waterways connected to the Murray River. Three species included in this community that occur in the Mallee are also listed under the EPBC Act (i.e. Murray Cod, Murray Hardyhead, Silver Perch).

(20) ‘Mallee Bird Community’ is EPBC listed (endangered) as the Mallee Bird Community of the Murray Darling Depression Bioregion. FFG listing is as the Victorian Mallee Bird Community.

Species identified as culturally significant to Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples or iconic to the general community are also considered a priority by this RCS, regardless of conservation status. While it is recognised that all Country and species are important to Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples, species of particular note for the region include Red Kangaroo, Quandong, Malleefowl, Black Swan, Murray Cod, River Red Gum, Emu Bushes, Garland and Flax Lily, and Bull Rushes. There are also several species the general community identify as being iconic to their local landscapes. Examples include Buloke Woodlands, Malleefowl, Plains Wanderer, Regent Parrot, Pink Cockatoo, Murray Cod and Carpet Python.

In providing the basis for much of our complex and unique biodiversity, the region’s terrestrial habitat is significant not only for the environmental values it supports; but also for the economic, social, and cultural services it provides. This includes resilience against land degradation, protection from extreme weather events, carbon storage, connections to Country, recreational opportunities, and positive landscape aesthetics.

Overall, the survival of many native plants and animals is directly dependant on the extent and condition of our terrestrial habitat; with native vegetation playing a critical role in mitigating the impact of threats such as salinity and erosion on our natural, cultural and productive landscapes.

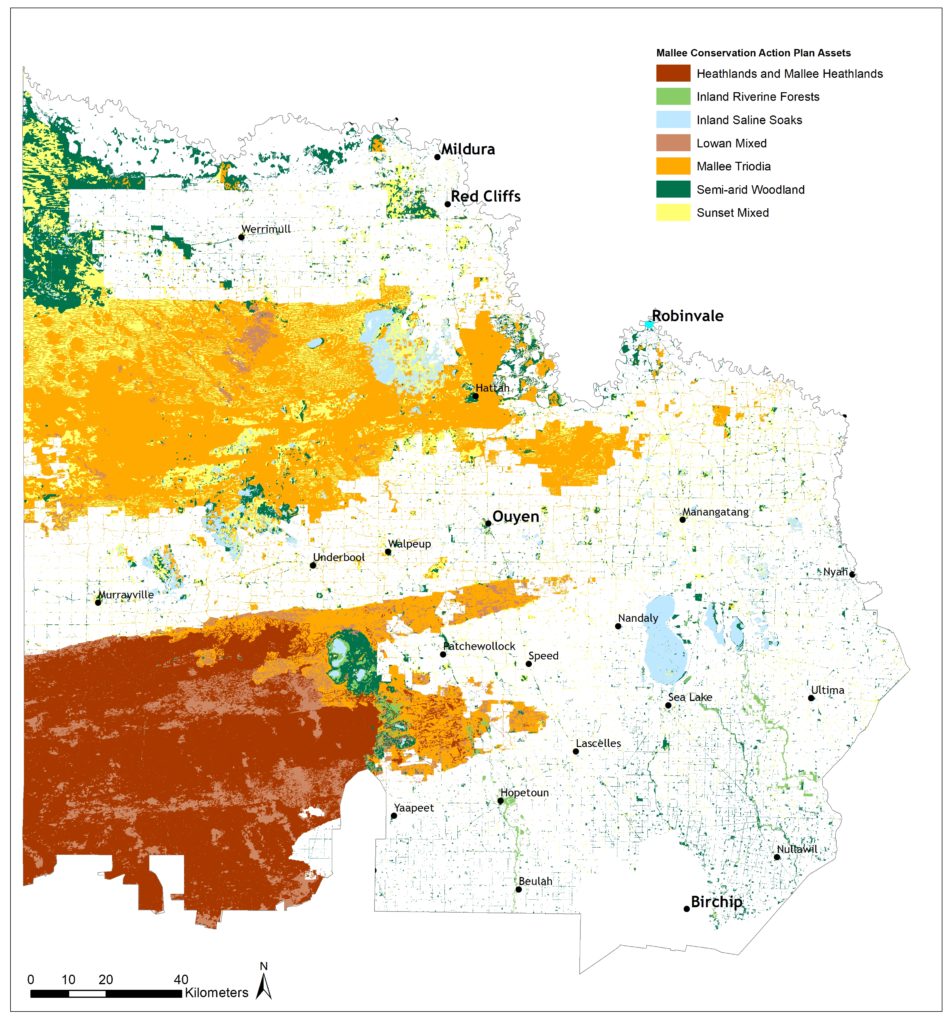

The terrestrial habitat of the Mallee is primarily defined by the prevailing native vegetation community at any particular location. In Victoria, these communities are classified into Ecological Vegetation Classes (EVCs). There are around 300 different EVCs in Victoria; 50 occur in the Mallee region.

EVCs can be further grouped into ecosystem classifications to represent vegetation communities that occur in similar types of environments (e.g. soil type, climate, topography) and which tend to show similar ecological responses to environmental factors such as disturbance (e.g. bushfire).

Application of this approach to group the Mallee’s terrestrial vegetation types identifies seven ecosystem classifications, reflecting the structural and compositional similarities of the constituent vegetation classes (Figure 15). Just over half (2,047,654 hectares) of the region’s native vegetation has been cleared since European settlement, particularly those vegetation communities growing on the more fertile alluvial soils (i.e. suitable for agriculture). Timber was also felled during early European settlement for the construction of both private and public infrastructure.

Large contiguous blocks of terrestrial habitat do however remain, predominantly in reserved areas such as Murray-Sunset and Wyperfeld National Parks, which are characterised by their infertile sandy soils. As such, these large remnant blocks do not represent the entire diversity of the region’s original habitat. Of the remaining native vegetation, only 12 percent occur on private land.

This section provides an overview on the current condition of biodiversity in the Mallee. State-wide and regional indicators have been applied to establish a baseline, and where available identify long term trends, from which progress against our medium-term (6-year) and long-term outcome targets for biodiversity can be determined.

Threatened species and communities

The 2018 State of the Environment report highlighted that a third of all of Victoria’s terrestrial plants, birds, reptiles, amphibians, mammals, invertebrates and ecological communities are threatened with extinction.

As of June 2021, Victoria’s Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (FFG Act) Threatened List included: 54 Extinct, 556 Critically endangered, 1,071 Endangered, and 303 Vulnerable species (21). Of these: 87 Critically endangered, 240 Endangered, and 60 Vulnerable species/communities have been recorded as occurring in the Mallee. At a national (EPBC) level, the region supports eight Critically endangered, 13 Endangered, and 18 Vulnerable species/communities (22).

Table 4 shows the number of flora and fauna species and communities currently listed as threatened under federal (EPBC) and state (FFG) instruments. A full listing of species/communities and their conservation status is provided in Appendix 5.

In general, historical habitat loss has been the primary circumstance for so many of our species and communities to be considered as threatened. This loss of habitat has not only compromised the abundance and distribution of our species, but has also increased the incidence

In general, historical habitat loss has been the primary circumstance for so many of our species and communities to be considered as threatened. This loss of habitat has not only compromised the abundance and distribution of our species, but has also increased the incidence and subsequent impact of other threatening processes (such as land and water salinisation, invasive plants and animals, altered hydrological regimes, soil erosion and constrained regenerative capacity).

It is difficult to provide an overall picture of the current condition of the region’s threatened species

and ecological communities. Some populations are comprehensively observed and reported on, while others remain somewhat cryptic due to insufficient resources to support systematic surveys, or the nature of the species itself. Without an understanding of the trajectory of a larger range of species and communities, the number of species listed as threatened and their associated conservation status will continue to be applied as a proxy indicator of condition.

Terrestrial habitat

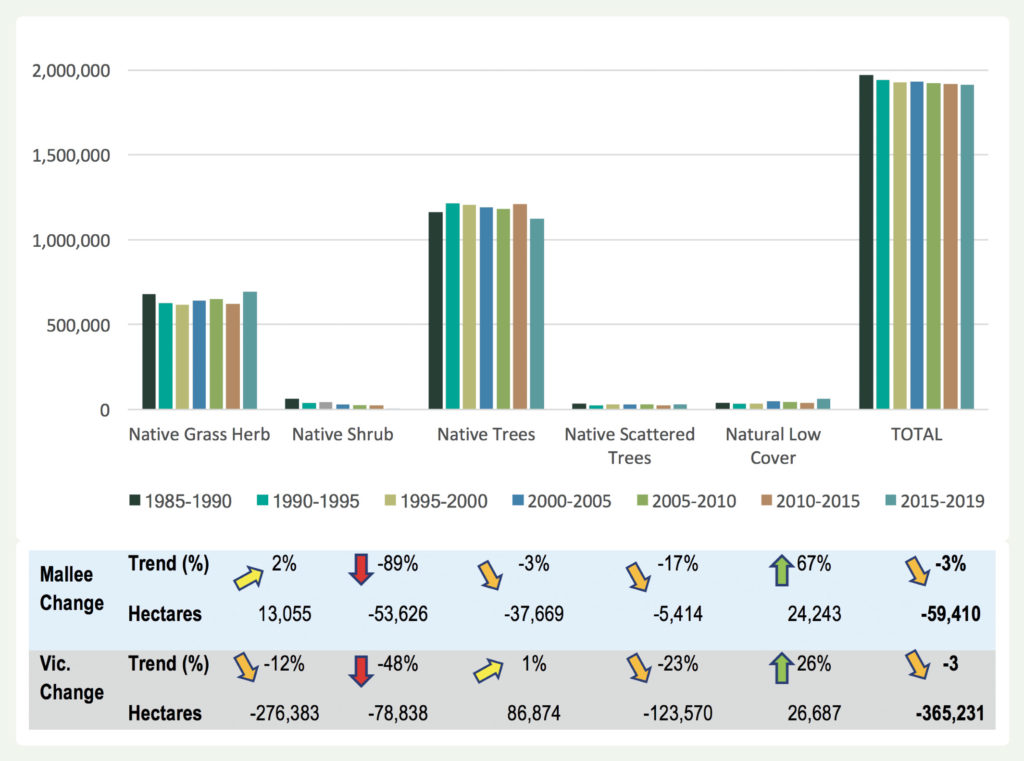

Native vegetation across the Mallee once covered some 3,919,887 hectares, of which 52 percent is estimated to have been cleared since European settlement. The region’s remaining vegetation has primarily been reserved in large parks such as Murray-Sunset, Big Desert, Wyperfeld and Hattah-Kulkyne, extensive tracts of state forests, and over 500 small reserves scattered throughout the agricultural area.

Remnants on private land, and the roadsides and rail reserves dissecting the region also represent significant areas of native vegetation. These are of particular importance for the threatened flora they contain and for the connectivity opportunities they provide to our region’s fauna.

Modelling of native vegetation extent in the region over the past 30 years indicates significant variation within different vegetation classes. Overall however, it is estimated that there has been a three percent decline in vegetation cover since 1985 (Figure 16).

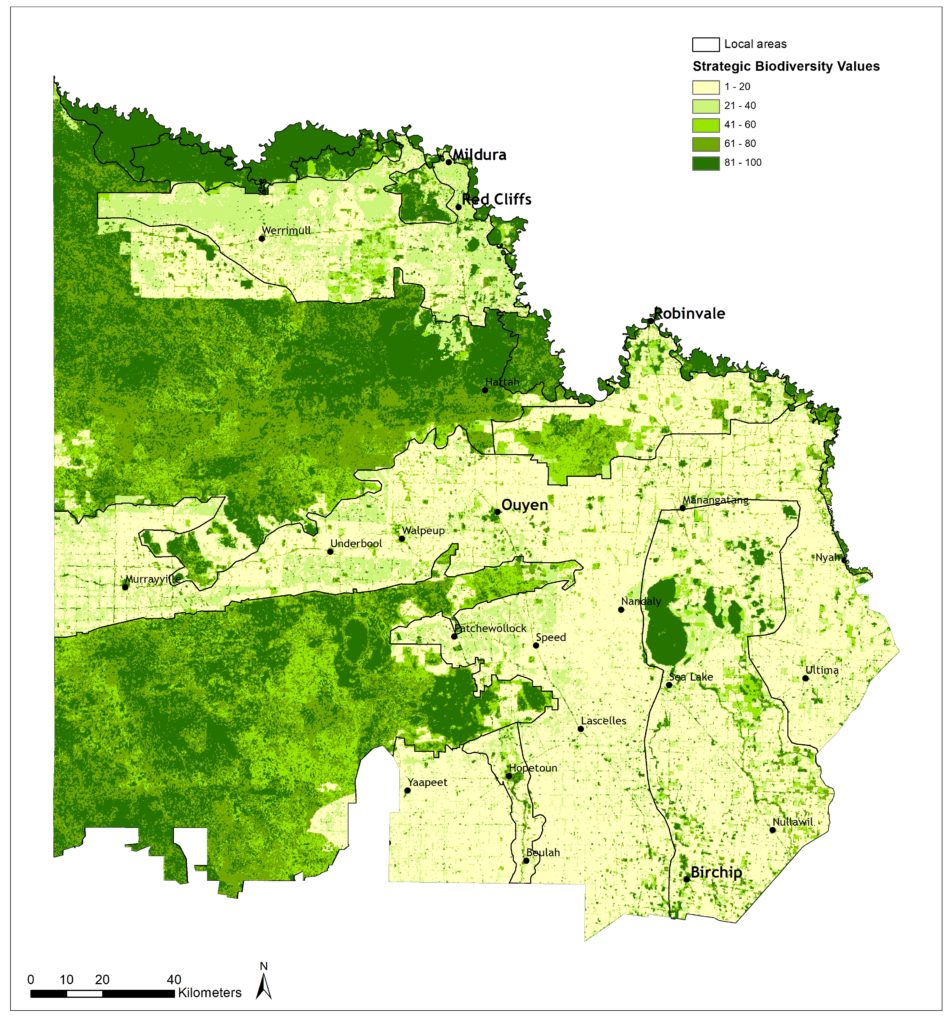

State-wide modelling on the relative contribution of these areas to the protection of the full range of Victoria’s biodiversity values demonstrates that a significant proportion of the Mallee has high importance for biodiversity conservation. Of particular value are our large tracts of public land, given the largely cleared and fragmented landscape in which they occur (Figure 17).

This Strategic Biodiversity Values (SBV v4.0) spatial tool ranks all locations across Victoria for their ability to represent threatened vertebrate fauna, vascular flora, and the full range of Victoria’s native vegetation (on a scale of 0 to 100). It combines information on important areas for threatened flora and fauna, levels of depletion, connectivity, vegetation types and condition to provide

a view of relative biodiversity importance of all parts of the Victorian landscape. This enables comparison of locations across the state, within the Mallee region, and at a landscape scale.

Overall, the 2020 condition and trajectory of native vegetation (i.e. tree cover, vegetation condition, and vegetation growth) in the Mallee is considered to be stable to improving when compared to a 20 year (2000–2020) average. All three indicators improved from 2019; largely in response to slightly better climatic conditions experienced over the winter to spring period (24).

Trends in measures of condition within major parks and reserves remain stable, if not improving as a result of management interventions undertaken over the past 30 years (e.g. reducing grazing pressure), and some large rainfall events experienced in the region over the same period (25). Within the more fragmented area of the landscape, remnant vegetation subjected to management interventions has also remained generally stable. Due to continuing threatening processes, declines in some measures of condition would however be expected within many remnants, especially those where threat mitigation actions have not occurred.

Management

The area over which targeted management actions are delivered in the Mallee has also been applied as a long- term indicator of biodiversity condition. Consideration of site-based (point of investment) monitoring of these works enables associated changes in threat incidence/impact and asset condition (where available) to be quantified and applied to broader assessments of the effectiveness of regional efforts to conserve biodiversity values.

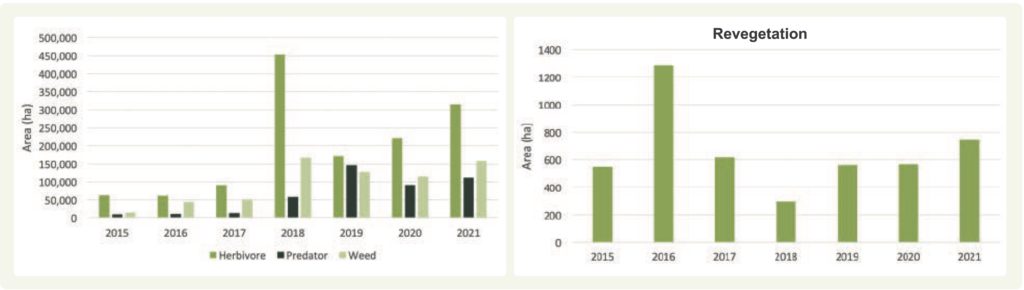

Data presented in Figure 18 represents works delivered through Mallee CMA programs over the past seven years. It does not however capture the significant areas of threat mitigation actions undertaken annually on public and private land through other funding initiatives, or by individual (e.g. private, volunteer) efforts (26). Ongoing assessments have identified both a reduction in threat processes and associated habitat improvements resulting from these works.

For example, long-term rabbit control programs in the Mallee continue to maintain numbers below the regional threshold of <1 per spotlight km required to support regeneration processes. In 2021, ongoing transect monitoring of rabbit activity within the Mallee’s four remnant rangeland communities reported 91 percent of the kilometres surveyed had one or less rabbits recorded (27). Site-based (annual) monitoring of targeted control programs identified that 61 percent of pre- treatment rabbit numbers were less than one rabbit/ha (range between 4 and 0 per ha); increasing to 88 percent of sites post-treatment (range between 3.5 and 0 per ha) (28).

Monitoring of a selection of revegetation sites identified that between 2011–2021, 49 percent of planted tubestock was recorded as surviving, and 69 percent of directly seeded sites report germination; figures which continue to improve as previous learnings are employed. Furthermore, over the medium-term (i.e. >5 years) revegetation sites are showing evidence of ecological functionality returning to the site. Specific changes recorded include: improved soil condition (i.e. reduced erosion); a reduction in threats (e.g., kangaroos, rabbits and herbaceous weed); evidence of habitat utilisation (i.e. movement/utilisation of species primarily birds using these areas as corridors); and improved ecosystem function (e.g. evidence of ongoing natural regeneration) (29).

(21) VAGO (Victorian Auditor-General’s Office). 2021. Protecting Victoria’s Biodiversity: Independent assurance report to Parliament, no. 266

(22) Victorian Biodiversity Atlas: Database filtered to include records for 1990 – 2021 period only.

(23) Note: Recent changes to the FFG Act Threatened list have removed duplication by establishing a single comprehensive list of threatened flora and fauna species. All non-statutory lists under the Victorian Threatened Species Advisory List have now been revoked (source: https://www.environment.vic.gov.au/conserving-threatened- species/threatened-list).

(24) Centre for Water and Landscape Dynamics (2021): 2020 Environmental Report Card – Mallee

(25) Parks Victoria: Conservation Action Plan for Parks and reserves managed by Parks Victoria, Mallee (2019).

(26) Addressing this information gap will be required under this RCS to support monitoring and reporting of progress against associated outcome and management targets.

(27) Parks Victoria (2021), Rabbit Transect Monitoring: unpublished data.

(28) Mallee CMA (2021), Rapid Rabbit Assessments, unpublished data.

(29) Mallee CMA (2021), Revegetation Monitoring, unpublished data.

This section outlines the major threats and drivers of change influencing the condition and management of biodiversity in the Mallee; core management and strategic directions that will guide delivery of our biodiversity related actions over the next 6-years; and the associated regulatory, policy and planning framework that informed their development.

Major threats and key drivers of change

Ongoing pressure from a range of long-term threats (e.g. climate variability, habitat loss, fragmentation, grazing pressure, competition from invasive weeds, introduced predators, inappropriate fire regimes, agricultural practices, recreational pressures, constrained regenerative capacity) and emerging threat processes (e.g. changing climate) are directly influencing the condition and resilience of Mallee biodiversity. Ongoing efforts to effectively manage these processes is vital to securing the long-term health of critical ecosystem processes and the services they provide to the region.

Conversely, there are also new initiatives that present the region with opportunities to improve how we plan for and deliver biodiversity conservation activities in the Mallee. These include participation in emerging carbon markets for biodiversity co-benefits, application of new technology, increased recognition of recreational and amenity values, and increasing self-determined participation and leadership of Traditional Owners.

How we respond to these threat processes and opportunities will play an important role in shaping the future trajectories of our native species, ecological communities and terrestrial habitat.

Further detail on the challenges, opportunities and major threats influencing Mallee biodiversity is provided in Section 1 (The Region – 4: Key Drivers of Change).

Aligned plans

Identification of the priority management and strategic directions detailed below has been informed by federal and state legislation, policies and strategies; regional strategies and action plans; and stakeholder priorities. The primary federal, state and regional instruments considered through this process are detailed in Appendix 2.

There is currently no overarching ‘whole-of-region’ plan that collates stakeholder strategic directions, priorities and targets for biodiversity conservation and management in the Mallee. For the purposes of this RCS, the Victorian Government plan for biodiversity (Biodiversity 2037) will be applied to fill this gap. Alignment with associated Biodiversity Response Planning processes will provide for regional interpretation and application.

Biodiversity related planning frameworks that focus on specific landscapes (i.e. not whole-of-region) are identified within their associated ‘Local Area’ (see Section 4). This includes Traditional Owner Country plans, site-based management plans, and individual stakeholder theme and/or landscape-based planning.

Management directions

In considering the current condition of Mallee biodiversity, the key drivers influencing this condition, associated planning instruments, and stakeholder priorities; four key principles to direct our management efforts have been identified. Specifically, that biodiversity programs focus on actions that will collectively support:

- Protection and restoration of existing terrestrial habitat for increased function and resilience

- Re-establishment of terrestrial habitat for improved landscape context (e.g. species composition and diversity patterns across habitats) and connectivity

- Specialised interventions required for the conservation of specific threatened species (terrestrial and aquatic)

- Improved amenity and recreational opportunities.

The habitat protection/restoration principle facilitates landscape-scale focused planning and delivery which benefits multiple species, rather than planning for native vegetation and individual species conservation in isolation. An approach which aligns with the Victorian Government’s Biodiversity 2037 premise that biodiversity management is more effective and efficient if synergies and potential negative outcomes are considered, particularly under a changing climate where adaptive capacity and landscape resilience is critical to ongoing conservation efforts. It is also recognised however that some endangered and critically endangered species will not benefit from this wider habitat focused landscape-scale approach, and will require specialised interventions.

In developing programs to deliver against these principles, the following priorities have been identified to inform how our management actions are planned and implemented:

- Community and government partnerships to support integrated cross tenure delivery

- Landscape scale interventions that reduce key threats and provide multiple species benefits

- Targeted/specialised interventions (where appropriate) that reduce key threats and provide location specific and/or single species benefits

- Maintaining previous investment where appropriate to ensure the ongoing effectiveness of significant works programs

- Ensuring that amenity and/or recreation focused activity complements existing natural and cultural values

- Applying seasonally adaptive, and where required (e.g. extreme events), responsive approaches

- Climate ready interventions to provide for improved resilience and adaptive capacity

- Collaborations to maximise the potential of carbon plantings to deliver biodiversity co-benefits

- Incorporation of cultural values, objectives, knowledge and practice; as self-determined by Traditional Owners.

Priority directions for building stakeholder, Traditional Owner and the broader community’s participation in and capacity for natural resource management, including biodiversity, are outlined in Section 3.5 (Community Capacity for NRM).

Priority directions for the protection of Traditional Owner/ First Peoples cultural values are outlined in Section 3.4 (Culture and Heritage).

Strategic directions

Mallee biodiversity is diverse and faces a complex suite of threats to its condition. Given the finite resources available to manage our terrestrial habitat and threatened species/communities, it is not feasible to expect that management actions to address all asset x threat interactions across the entire region can be implemented over the life of this RCS. To help ensure we achieve the ‘best’ results with the resources available, a targeted delivery framework is required.

Targeting Habitat Focused – Landscape Scale Delivery

To inform this targeted approach, work undertaken by DELWP to help integrate and compare information on the expected benefits and indicative costs of conservation actions across species and locations has been applied. Strategic Management Prospects (SMP) is a state-wide spatial modelling tool that integrates and simultaneously compares information on biodiversity values, threats, effectiveness of management actions, and indicative costs of management actions for biodiversity across Victoria. This allows for the identification and prioritisation of management actions according to their cost-effectiveness (i.e. which) and their relative contribution to net conservation outcomes across all species (i.e. where) (30).

The SMP tool was utilised to identify priority locations in the Mallee for the implementation of management actions contributing to state-wide (Biodiversity 2037) targets for weed control, herbivore control, pest predator control, and the re-establishment of revegetation.

Individual action x location interactions were then reviewed by regional stakeholders and further refined to incorporate local priorities and aspirations. Maps showing the results of these analyses (i.e. regional priorities) for each management action type are provided in Appendix 6.

In the absence of SMP modelling for revegetation actions seeking to restore existing remnants (e.g. supplementary planting), locations will be identified on site needs (e.g. limited regenerative capacity of existing vegetation) x stakeholder priority basis, as part of landscape scale assessments.

Similarly, permanent protection actions will be targeted to underrepresented vegetation on private land to align with the National Reserve System’s guidelines for establishing a comprehensive, adequate and representative reserve system.

Targeting Specialised Interventions

Threatened, culturally significant, or iconic species and communities identified as requiring specialised or site specific interventions are considered separately; with conservation status and Traditional Owner/local community priorities, along with expert conservation advice (e.g. EPBC Recovery plans) being key drivers in the identification of both species and management actions.

Decision support tools available from the DELWP NatureKit site, including habitat distribution and importance models, and specific need analysis for a number of listed species can also help inform this process.

Additional Considerations

To provide for continuous improvement and support adaptive management processes; ongoing application of local expertise, Traditional Owner knowledge, and best available science is also fundamental to the RCS biodiversity delivery framework.

(30) Strategic Management Prospects can be accessed online through the DELWP NatureKit site.

This section outlines the medium-term (6-year) and long-term (20-year) outcome targets that regional stakeholders have collectively set for biodiversity management and conservation across the Mallee.

Protecting Victoria’s Environment: Biodiversity 2037 establishes five management targets to be achieved over the 20-year timeframe of the strategy. The proportion of these targets occurring across each of Victoria’s ten catchment area was also determined to establish interim (10-year) and final (20-year) allocations for each region. Table 5 details the interim targets allocated to the Mallee through this process.

Our medium-term outcome targets for biodiversity (Table 6) have been developed to align with, and demonstrate how the Mallee RCS will contribute to these Biodiversity 2037 targets over the 2022–28 period. RCS targets for weed control, herbivore control, pest predator control, revegetation and permanent protection were determined through consultation with stakeholders and represent what key partners can confidently deliver over the next six years.

Spatial representations of the region’s priorities for weed control, herbivore control, pest predator control, and the re-establishment of revegetation are provided in Appendix 6 (31).

Delivery against these targets will be undertaken as part of the RCS’s integrated catchment management (ICM) – landscape-scale approach to NRM. Detail on specific management actions and targets to be implemented within individual landscapes, and the local stakeholders that will contribute to their delivery is provided in Section 4 (i.e. Local Areas).

(31) Does not include priority locations for targets relating to revegetation within existing remnants (i.e. restoration) or permanent protection on private land (see Strategic Direction section above for further context).