Vision

Waterways are healthy, resilient, and being managed for shared benefits*.

Scope

Rivers, streams, their tributaries, and surrounding riparian land (including the floodplain), and individual wetlands, wetland complexes, and their associated floodplain ecosystems (including groundwater dependent ecosystems and the groundwater flow systems and aquifers they are reliant on)#.

* Shared benefits are achieved when waterway management actions delivering against environmental and economic requirements are also supporting cultural and recreational outcomes.

# The threatened species and ecological communities supported by aquatic and riparian habitat are considered within the Biodiversity theme; and groundwater resources utilised for human use such as irrigation or stock and domestic water supply within the Agricultural Land theme. Building community knowledge of, and participation in, waterway management is covered by the Community Capacity for NRM theme.

The Mallee contains some 1,600 kilometres of rivers/creeks and over 900 wetlands. Many of these waterways have been recognised as nationally and internationally important for the environmental, social, cultural and economic values they provide. This includes one Ramsar site (Hattah-Kulkyne Lakes); one Heritage River (Outlet Creek and Wirrengren Plain section of Wimmera River); and 16 sites listed on the Directory of Important Wetlands, Australia (e.g. Lindsay Island, Belsar Island, Kings Billabong, Lake Tyrrell and Raak Plain).

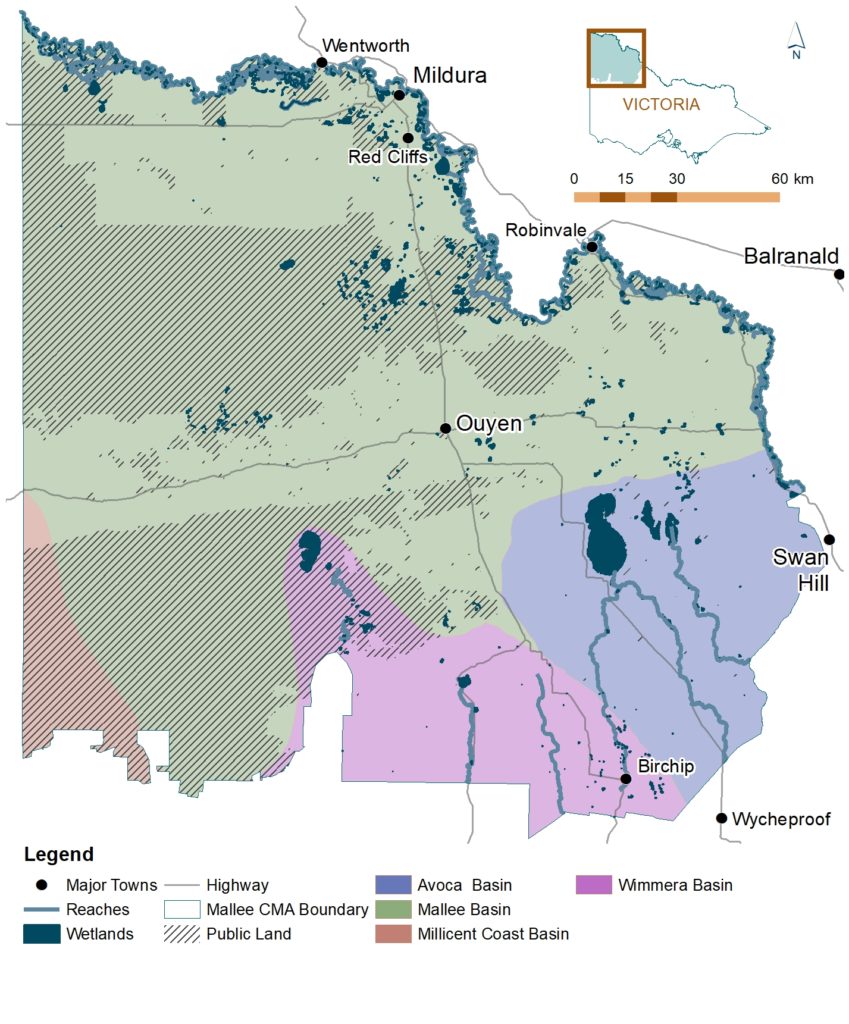

Mallee rivers and creeks can be divided into three main groups according to the river basin in which they are located; the Mallee, Avoca or Wimmera Basin (32) (Figure 19).

The Mallee Basin contains the Murray River which forms the northern boundary of the region, as well as the boundary between Victoria and New South Wales (NSW). While the main river channel lies in NSW, Victoria is responsible for the management of its southern floodplain from the 1881 winter level water mark. Wallpolla Creek and Lindsay River are the primary anabranch systems, both occurring downstream of Mildura.

In the south, north-flowing intermittent streams of the Wimmera River System, including the Yarriambiack and Outlet Creeks, terminate in a number of ephemeral wetland complexes such as the Wirrengren Plain, Lake Coorong and Lake Lascelles. In the south-east, two effluent streams of the Avoca River system, Tyrrell and Lalbert Creeks, empty into a number of large terminal saline wetlands, including lakes Timboram and Tyrrell.

Dunmunkle Creek represents two separate waterways, a southern section commencing in the Wimmera catchment flows north towards Lascelles; and northern section commencing as a broad shallow area south of Birchip flows north-west, then north-east through Green Lake before joining Tyrrell Creek and entering Lake Tyrrell in the Avoca Basin.

Mallee wetlands are diverse and include: riverine wetlands, natural saline wetlands fed by groundwater, shallow depressions in the south of the region filled by local catchment run-off, and artificially maintained wetlands and lakes.

Collectively, our 900 plus wetlands occupy some 50,000 hectares of the landscape; with 84 percent occurring on public land, and the remaining located on freehold land historically used primarily for either dryland farming or irrigated horticulture.

Semi-permanent saline wetlands are the most prevalent wetland type in the Mallee. These wetlands have increased in both number and area since European settlement due to altered hydrological regimes, clearing of native vegetation, changes in surrounding land use, and the use of natural wetlands and low-lying areas for salinity management.

Wetlands associated with the Murray River or its anabranches are primarily seasonal, intermittent or ephemeral wetlands that fill when the Murray River floods, although under natural or pre-regulation conditions some would have been inundated more or less permanently. Most riverine wetlands are freshwater meadows, marshes and permanent open freshwater wetlands, characterised by trees such as River Red Gum and Black Box. Only a few saline wetlands occur along the Murray River, primarily the result of secondary salinisation caused by disposal of saline irrigation drainage water or intrusion of saline groundwater.

Wetlands in the centre and south east of the region are mostly saline systems (salinas and boinkas) that are typically associated with fault line influences and natural groundwater discharge sites. These wetlands are generally semi-permanent and are characterised by salt tolerant flora. Large terminal saline wetlands such as Lake Tyrrell and Timboram are significant features of the region.

In the south-west of the region, wetlands are generally freshwater marshes restricted to the Outlet Creek system within Wyperfeld National Park; although a few saline wetlands do occur northwards of Outlet Creek.

The far south contains almost a quarter of the Mallee’s most depleted wetland type, freshwater meadows. Historically these ephemeral wetlands would have been inundated by local catchment runoff, however the hydrology of this area has been significantly altered through the historical development of the area for agriculture.

As defining features of the region, Mallee waterways and floodplains are significant not only for the specialised habitat and environmental values they support; but also for the broader ecosystem, social, cultural and economic services they provide. This includes, refugia and connectivity opportunities within largely cleared landscapes; carbon storage, salt interception, nutrient cycling, and water purification; replenishment of connected groundwater systems to support associated groundwater dependant ecosystems; flood mitigation, water supplies and storage for irrigation, industrial, domestic and stock use; connections to Country; diverse tourism and recreational opportunities; and positive landscape aesthetics.

(32) The Mallee also contains a portion of the Millicent Coast Basin, there are however no waterways contained within this Basin in the Mallee CMA region.

This section provides an overview on the current condition of waterways in the Mallee. State-wide and regional indicators have been applied to establish a baseline, and where available identify long term trends, from which progress against our medium-term (6-year) and long-term (20-year) outcome targets for waterways can be determined.

Rivers

Periodic assessments on the condition of Mallee rivers and streams are conducted as part of state-wide Index of Stream Condition (ISC) and Index of Wetland Condition (IWC) monitoring programs.

Condition was measured by the ISC according to five sub-indices (hydrology, physical form, streamside zone, water quality and aquatic life) that contain 23 key indicators, to provide a summary of the extent of change from natural or ideal conditions.

Assessments of river condition using the ISC were first conducted in 1999 and again in 2004 and 2010. In general, this monitoring identified that no major changes occurred to the condition of these waterways over this timeframe. While no general improvement was detected, overall deterioration appears to have been controlled (33).

This is an encouraging result given the data collected in the third assessment period coincided with the end of the severe Millennium Drought in south-eastern Australia. It is assumed that the targeted threat mitigation actions undertaken in the region over this period played an important role in minimising the impact of the drought and that they should assist with future improvements in condition under favourable climatic conditions.

The most recent (2010) ISC monitoring assessed 73 individual reaches in the region, with four percent of stream length identified as being in moderate condition and the remaining as being in poor (64%) or very poor (32%) condition.

The proportion of reaches with poor scores was directly influenced by the ISC hydrology sub-indices attributing low scores for seasonally regulated flows. The high number of reaches subject to modified flow regimes to meet irrigated agriculture demands is subsequently reflected in overall condition scores.

Streamside vegetation (i.e. woody vegetation within 40 metres of rivers edge) was found to be in good condition for the majority (59%) of reaches, with the remainder in either excellent (1%), moderate (34%) or poor (6%) condition. Low scores were attributed predominantly to narrow, fragmented streamside vegetation, while the moderate and good scores reflected diverse streamside vegetation and the absence of willows.

Physical condition (i.e. bank condition, instream woody habitat, artificial barriers) was assessed as moderate for 67 percent of reaches, remainder ranging from poor (11%) to good (16%) and excellent (6%). The presence of downstream fish barriers in 96 percent of the assessed reaches reduced overall scores for this indicator.

Wetlands

The Index of Wetland Condition (IWC) provided a measure of condition across a subset of Victoria’s high value wetlands according to six sub-indices (wetland catchment, hydrology, water properties, soils, biota, and physical form) comprised of 16 different measures. Monitoring was designed to allow for the identification of significant changes in wetland condition from a theoretical reference condition (i.e. unmodified by human impacts associated with European settlement).

The IWC was applied in the Mallee between spring 2009 and autumn 2010 following a period of extended drought. Monitoring was conducted on 79 wetlands considered to be of high conservation value and a priority for management. Over half (53 percent) of the assessed wetlands were identified as being in good or excellent condition, 42 percent as being in moderate condition, and only five percent as being in poor or very poor condition.

It is also noted that although a high number of wetlands were assessed as being in good condition, there was significant variation evident in condition at the sub-index level. For example, 89 percent of wetlands were identified as having poor or very poor hydrology condition, while 96 percent had good to excellent physical form (34).

While the IWC is not currently scheduled to be repeated, it does provide the region with detailed benchmarks in specific indicators of condition, from which future change from natural or ideal conditions can be determined at both the site (i.e. individual wetland) and landscape (i.e. representative wetlands) scale.

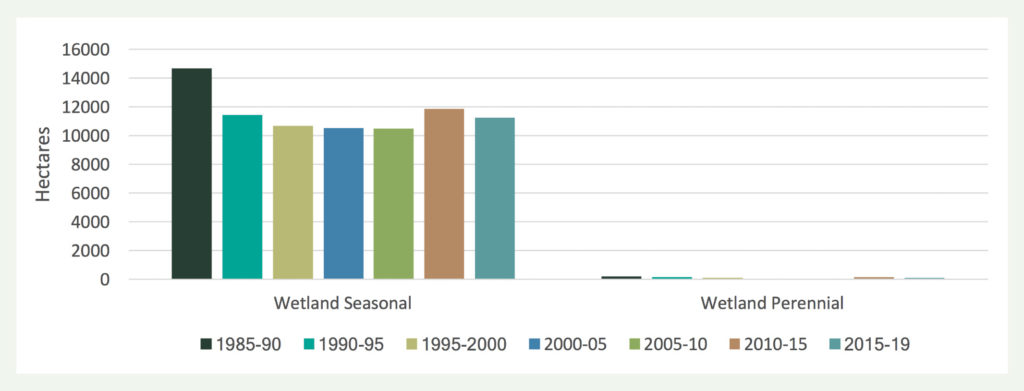

Modelling of changes in wetland extent over the past 30 years indicates an overall decrease in the area of wetlands across the region, with the area of seasonal wetlands declining by 23 percent (3,431 ha) between 1985 and 2019; and perennial wetlands by 53 percent (88 ha) over the same period (Figure 20).

Figure 20 | Extent (ha) of Wetland Cover Classes in the Mallee CMA region over time (source: DELWP, Victorian Land Cover Time Series).

Groundwater

Trend analysis from 2013 to 2021 of 549 regional groundwater bores monitored for water level and salinity has identified no trend for either indicator over the past eight years (i.e. neither rising nor falling) (35).

Ongoing monitoring of regional groundwater trends allows for the identification of changes in the natural water balance through either extraction (e.g. irrigation), or accelerated recharge and/or discharge processes resulting from land use and land management changes. These changes can directly influence our aquatic, riparian and terrestrial ecosystems through associated variations in aquifer levels, water quality and soil chemistry. This can be especially significant for ecosystems that rely on groundwater to meet all or some of their water requirements (i.e. Groundwater Dependent Ecosystems). In the Mallee this includes wetlands with both fresh and saline groundwater dependency, rivers, and some terrestrial vegetation communities.

The condition of groundwater utilised for human use such as irrigation or stock and domestic water supply is outlined in Section 3.3 (Agricultural Land).

Management

The area over which targeted management actions are delivered in the Mallee has also been applied as a long-term indicator of waterway condition. Consideration of site based (point of investment) monitoring of these works enables associated changes in threat incidence/ impact and asset condition (where available) to be quantified and applied to broader assessments of the effectiveness of regional efforts to conserve waterway and floodplain values.

Data presented in Table 7 represents works delivered through Mallee CMA programs over the past seven years. It does not however capture the significant areas of threat mitigation actions undertaken annually on public and private land through other funding initiatives or by individual (e.g. private, volunteer) efforts (36).

Ongoing site-based assessments have identified both a reduction in threat processes and associated condition improvements resulting from these works.

For example, significant areas of inundation being achieved through environmental watering actions is having a demonstrable impact on waterway connectivity and both aquatic and riparian habitat condition. This includes the Hattah Lakes and Lindsay-Mulcra-Wallpolla Living Murray Icon Sites, where long-term monitoring (2006 to 2021) has identified that several measured indicators of environmental condition (i.e. River Red Gum, Black Box, wetland and floodplain vegetation, lignum, fish and waterbirds) continue to improve as a result of water application and associated works programs, with progress against the stated ecological objectives (condition targets) for each of these indicators recorded in 2020–21 (37), (38).

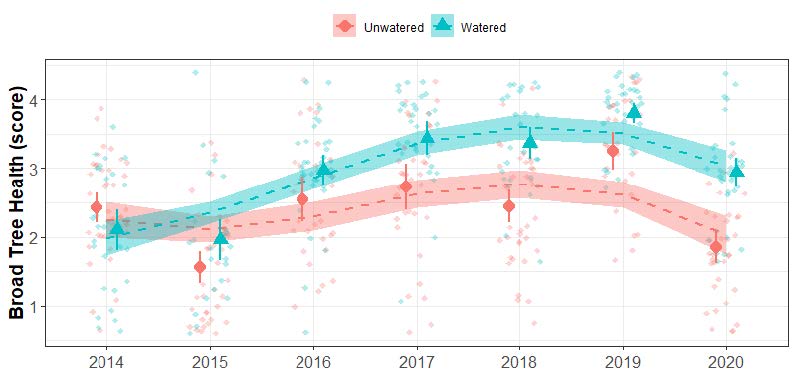

Figure 21 | Raw Black Box health data means (± 95% confidence interval) for each year sampled at the unwatered (red circles) and the 2014, 2016, 2017-18 and 2019 watered (blue triangles) case study sites. Individual points (jitter) and associated loess smooth lines show trends in the raw data based on watering (unwatered – red; watered – blue) (Moxham et al. 2020).

Water availability in the form of both rainfall and flooding are key drivers of plant community composition. Responses to flooding indicate while systems benefit from the environmental water deliveries, the timeframes over which this change occurs can vary according to individual communities and metrics. For example, long-term intervention monitoring at Hattah Lakes comparing watered and unwatered sites is reporting a positive response in Black Box health across the watered sites after one environmental watering event, with subsequent events further improving tree health (39) (Figure 21). Inundation of River Red Gum communities for between 50-60 days during spring and early summer was found to improve canopy condition by between 10 and 30 percent (40).

While the majority of the region’s long-term environmental watering monitoring programs are focused on The Living Murray (TLM) sites (Hattah and Lindsay-Mulcra-Wallpolla), this evidence base does support the assumption that positive outcomes are also being achieved at other watered sites. Given the scale and scope of environmental watering events delivered across the region over the past decade, it is anticipated the extent of these impacts is also relatively significant outside of the TLM sites.

Targeted threat mitigation works (e.g. invasive plant and animal management) are further securing environmental outcomes achieved by recent environmental watering events, and protecting priority riparian landscapes. Key examples of quantifiable reductions in threat extent include: Long-term rabbit control programs within priority riparian landscapes continuing to maintain numbers below the regional threshold of <1 per spotlight km required to support regeneration processes (41); and the diversity of invasive plants at Hattah Lakes being the second lowest recorded over the seven-year monitoring period (2013-20), with targeted works to control invasive species undertaken over an extended period having a high level of success (42).

Overall, the condition of Mallee waterway’s is considered to be stable to improving, with evidence that management actions will have a positive impact in the longer term.

(33) Department of Environment and Primary Industries (2013), Index of Stream Condition: The third benchmark of Victorian river condition

(34) Papas, P and Maloney, P (2012): Victoria’s wetlands (2009- 2011): state wide assessments and condition monitoring.

(35) Mallee CMA (2021), unpublished data.

(36) Addressing this information gap will be required under this RCS to support monitoring and reporting of progress against associated outcome and management targets.

(37) Ecology Australia (2021) The Living Murray Condition Monitoring, Lindsay-Mulcra-Wallpolla 2020-21, Part A (Main Report).

(38) Ecology Australia (2021) The Living Murray Condition Monitoring, Hattah Lakes 2020-21, Part A (Main Report).

(39) Moxham C., et.al. (2020) The Living Murray Hattah Lakes Intervention Monitoring: Impact of Environmental Watering on Black Box health, reproduction and recruitment – Final Report 2020. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research, Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Heidelberg, Victoria.

(40) Moxham, C. and Gwinn, D. (2021). Hattah Lakes floodplain tree condition: Modelling tree responses to environmental watering. Unpublished Report. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research, Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Heidelberg, Victoria

(41) Parks Victoria (2019). Spotlight Transect Scores – Hattah Area Autumn 2021.

(42) Moxham C., Duncan M., Leevers D. and Farmilo B. (2020) The Living Murray Hattah Lakes Intervention Monitoring

This section outlines the major threats and drivers of change influencing the condition and management of waterways in the Mallee; core management and strategic directions that will guide delivery of our waterway related actions over the next 6-years; and the associated regulatory, policy and planning framework that informed their development.

Major threats and key drivers of change

Mallee waterways continue to be threatened by a range of pressures which can directly influence their environmental condition, and therefore their capacity to provide the environmental, social, cultural and economic services we value.

The major threats to our waterways are those that impact on one or more of their core environmental attributes, specifically: habitat, water quality, flows, and connectivity. This includes processes such as altered hydrological regimes, land and water salinisation, erosion, invasive plants and animals, habitat loss and fragmentation, and recreational pressures.

External factors such as climatic conditions (both variability and change) and water availability are also key determinants of both the effectiveness of our management actions and the long-term health of our waterways that will require ongoing attention and adaptive management responses.

Conversely, there are also initiatives that present the region with opportunities to improve how we plan for and deliver waterway management activities in the Mallee. These include participation in emerging carbon markets for riparian and aquatic habitat co-benefits, application of new technology, increased recognition of recreational and amenity values, and increasing self-determined participation and leadership by Traditional Owners.

How we respond to these threat processes and opportunities will play an important role in shaping the future trajectory of waterway health in the Mallee.

The establishment of new infrastructure that allows for environmental water to be delivered more efficiently and effectively across the floodplain will also directly influence the region’s future waterway management outcomes. As part of the Victorian Murray Floodplain Restoration Project (VMFRP), infrastructure construction (e.g. flow regulators, containment banks) is being planned across seven sites (Lindsay Island, Wallpolla Island, Hattah Lakes, Belsar Yungera, Burra Creek, Nyah and Vinifera) in consultation with local communities, Traditional Owners and other stakeholders. When complete, works will support improved environmental outcomes across some 12,669 hectares of priority floodplain habitat and help deliver against the Murray Darling Basin Plan’s water recovery targets.

Further detail on the challenges, opportunities and major threats influencing Mallee waterways is provided in Section 1 (The Region – 4: Key Drivers of Change).

Aligned plans

Identification of the priority management and strategic directions detailed below has been informed by federal and state legislation, policies and strategies; regional strategies and action plans; and stakeholder priorities. The primary federal, state and regional instruments considered through this process are detailed in Appendix 2.

The Mallee currently has two overarching plans that collate stakeholder strategic directions, priorities and targets for waterways: The Mallee Waterway Strategy (2014–22) (43); and the Mallee Floodplain Management Strategy (2018–28).

Waterway related planning frameworks that focus on specific landscapes (i.e. not whole of region) are identified within their associated ‘Local Area’ (see Section 4). This includes Traditional Owner Country plans, site- based management plans, and individual stakeholder theme and/or landscape- based planning.

Management directions

The current condition of Mallee waterways, key drivers influencing this condition, associated planning instruments, and stakeholder priorities have directly informed the development of six key principles to direct our efforts. Specifically, that waterway management programs focus on actions that will collectively support:

- Protection and restoration of aquatic and riparian habitat for increased function and resilience

- Appropriate water regimes and improved connectivity for enhanced environmental, social and cultural benefits

- Water quality benefits and appropriate responses to threatening events (both natural and pollution based)

- Improved amenity and recreational opportunities

- Improved liveability and resilience of urban areas

- Enhanced mitigation of regional flood risks.

This approach focuses on protecting and improving the key environmental attributes of Mallee waterways on the basis that this will support increased capacity to deliver environmental, social, cultural and economic benefits. In developing programs to deliver against these principles, the following priorities have been identified to inform how our management actions are planned and implemented:

- Community and government partnerships to support integrated cross tenure delivery

- Landscape scale interventions that reduce key threats and provide whole of system benefits

- Targeted/specialised interventions (where appropriate) that reduce key threats and provide location and/or issue specific benefits

- Incorporation of cultural values, objectives, knowledge and practice; as self-determined by Traditional Owners

- Maintaining previous investment where appropriate to ensure the ongoing effectiveness of significant works programs

- Applying seasonally adaptive, and where required (e.g. extreme events), responsive approaches

- Climate ready interventions to provide for improved resilience and adaptive capacity

- Providing shared benefits (i.e. recreational and cultural outcomes) that complement environmental and economic requirements

- Applying integrated water management (IWM) approaches to best utilise all urban water sources (e.g. rainwater, stormwater, wastewater) for environmental, social and economic outcomes.

Priority directions for building stakeholder, Traditional Owner and the broader community’s participation in and capacity for natural resource management, including waterways, are outlined in Section 3.5 (Community Capacity for NRM).

Priority directions for the protection of Traditional Owner/ First Peoples cultural values are outlined in Section 3.4 (Culture and Heritage).

Strategic directions

Mallee waterways face a complex suite of threats to their condition. Given the finite resources available to manage our rivers and wetlands, it is not feasible to expect that management actions to address all of these asse x threat interactions across the entire region can be implemented over the life of this RCS. To help ensure we achieve the ‘best’ results with the resources available, a targeted delivery framework is required.

The asset-based approach established by the Mallee Waterway Strategy (MWS) will also be applied by the RCS to identify priority threat x location interactions for waterway related actions.

The MWS identifies 216 waterways as a priority for management through the application of the following filters:

- Environmental, social, cultural and economic values

- Alignment with region’s long-term goals

- Threat severity and risk

- Technical feasibility of available management responses.

The associated value, threat, risk, and feasibility assessment scores for each individual waterway was then used to identify, rank, and categorise (i.e. high, medium, low) 216 waterways as a priority for management.

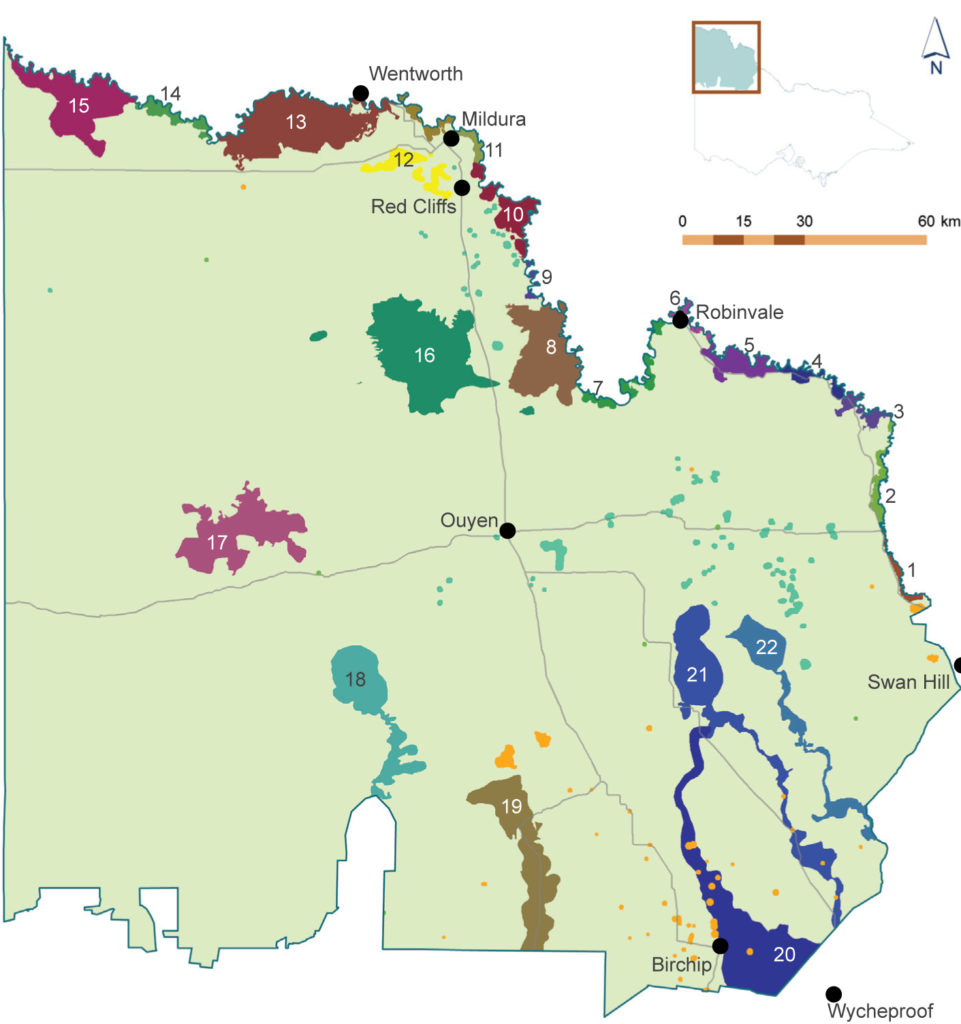

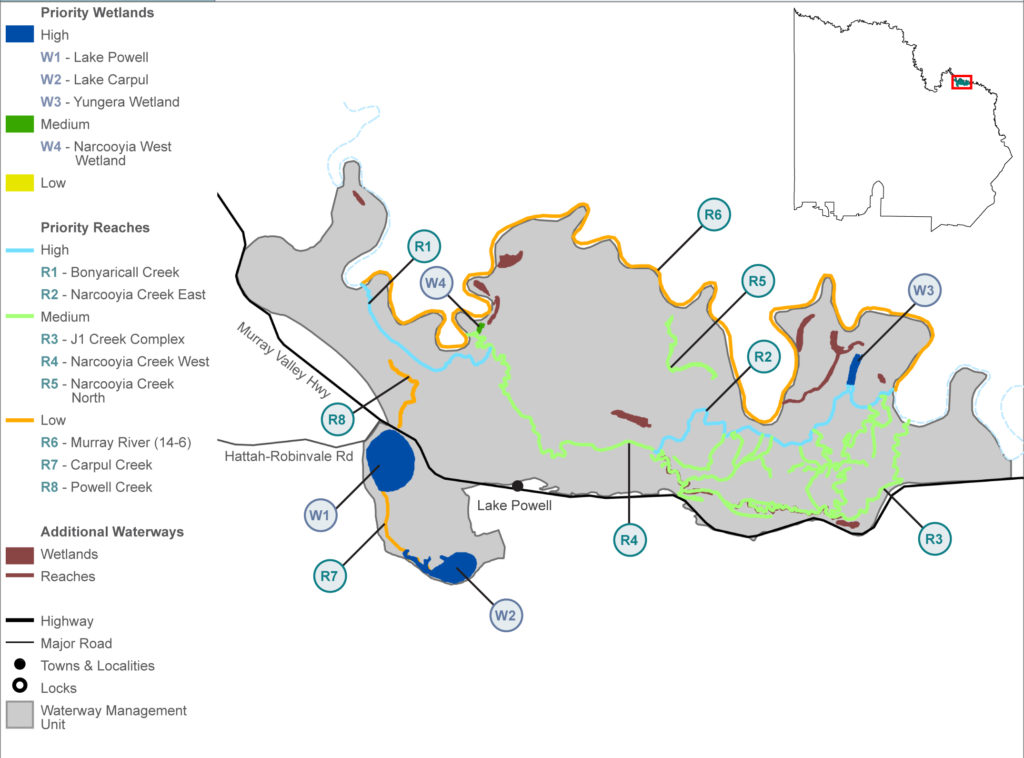

Under this framework, each of the region’s wetlands and reaches was grouped into 23 waterway management units (WMUs) which recognise their interconnectedness and the commonality of threats impacting on their values (Figure 22). Of these, 22 WMUs are represented by discrete geographic locations and one encompasses the region’s dispersed wetlands assets with four sub-classifications according to type (i.e. freshwater, saline natural, saline irrigation drainage, and artificial supply and sewage).

Figure 22 | a) Waterway Management Units established by the Mallee Waterway Strategy (2014-22); and b) example of waterway prioritisation within a Waterway Management Unit (Belsar Yungera).

Figure 22 | a) Waterway Management Units established by the Mallee Waterway Strategy (2014-22); and b) example of waterway prioritisation within a Waterway Management Unit (Belsar Yungera).

The integrated planning and implementation framework facilitated by these WMU’s allows for strategic planning outcomes and landscape scale/whole of system benefits to be achieved, while applying an asset-based approach (i.e. targeting effort to highest priority waterways). Future works will target high and medium priority waterways in the first instance; with works on low priority waterways subject to funding and, in some cases, further feasibility assessments.

It is important to note that priority waterways and their associated categories developed through this process relate to a waterway’s ranking with regard to future management activities being undertaken to reduce threats to their values. It is not an indication of the importance of each waterway.

To provide for continuous improvement and support adaptive management processes, ongoing application of local expertise, Traditional Owner knowledge, and best available science is also fundamental to the MWS and RCS waterway delivery frameworks.

(43) Review and renewal processes for the Mallee Waterway Strategy commenced in 2022.

This section outlines the medium-term (6-year) and long-term (20-year) outcome targets that regional stakeholders have collectively set for waterway management across the Mallee.

Our medium-term outcome targets for waterways have been developed to align with regional planning and reporting frameworks, and demonstrate how the Mallee RCS will contribute to state-wide indicators (Table 8).

Delivery against these targets will be undertaken as part of the RCS’s integrated catchment management (ICM) – landscape-scale approach to NRM. Detail on the specific management actions and targets to be implemented within individual landscapes, and the local stakeholders that will contribute to their delivery is provided in Section 4 (i.e. Local Areas).