Vision

Connected and resilient communities leading positive change across our natural, cultural and productive landscapes.

Scope

The inherent knowledge, skills and motivation that the community has for effective and sustainable natural resource management (where ‘community’ encompasses all land managers, Traditional Owners, organisations, groups and individuals contributing to NRM related activity across the region).

People of the Mallee are at the heart of the current and future management of our natural, productive and cultural landscapes.

Natural resource management (NRM) is a cooperative endeavour between government, industry and the broader community; with effective action requiring effective partnerships. To maintain these partnerships and achieve the goals of this RCS, a well-informed community with the skills and confidence to identify, direct and implement change is essential.

Our communities’ capacity is defined by their characteristics and resources which, when combined, determine their ability to identify, evaluate and address key issues.

In a natural resources context, community capacity involves the capability of Mallee communities to: work cooperatively; apply economic resources; use networks; and gain knowledge to achieve NRM outcomes. It is dependent not only on the financial, physical and natural resources contained within a community, but also its social resources.

The Mallee has a proud history of the community generating and implementing innovative and complex NRM projects and plans. Examples of the diverse range of stakeholders involved in NRM in the Mallee includes private landholders, government organisations, Traditional Owners/First Peoples, Landcare groups, citizen science based groups, ‘Friends of’ groups, community reference and advisory groups, Committees of Management, industry based groups, sporting and other special interest groups, schools, and private businesses.

In managing 62 percent of the region, private landholders continue to make significant individual contributions to the condition of our natural and productive landscapes through the implementation of both targeted stewardship focused actions (e.g. revegetation, stock containment, pest plant and animal control), and ongoing adoption of best management practice across both dryland (2.4 million hectares) and irrigated (88,000 hectares) landscapes.

Public land managers (i.e. Parks Victoria, DELWP, Local Government, VicTrack, VicRoads) are responsible for the remaining 38 percent of the region; including, National Parks, State Forests, roadside and rail reserves, and smaller (e.g. conservation, recreation) reserves scattered across the region. A number of voluntary committees of management also have responsibilities for a number of these smaller Crown land reserves.

Traditional Owner groups represent the rights and interests of First Nations’ communities in the management of Country through both the actions they undertake and their participation in regional NRM partnerships. Traditional Owner groups in the Mallee include Barengi Gadjin Land Council Aboriginal Corporation, First People of the Millewa Mallee Aboriginal Corporation, Gilbie Aboriginal Corporation, Murray Valley Aboriginal Corporation, Latji Latji Mumthelang, Nyeri Nyeri, Tati Tati, Wadi Wadi, Weki Weki, Wemba Wamba and Werigia. The diversity in Aboriginal representation across the region is also recognised, with input from broader stakeholders and partnership opportunities supported through community-based forums and reference groups.

Landcare groups play a major role in harnessing and promoting the interests of local communities in NRM issues. Each group provides a connection between the individual managers of separate properties and the wider community; increasing awareness of conservation issues, encouraging coordinated effort, and providing access to shared resources.

The region’s industry-based groups such as Mallee Sustainable Farming, Birchip Cropping Group, Murray Valley Winegrowers Inc., Almond Board of Australia, Dried Fruits Australia, Australia Table Grape Association, and the Victorian Farmers Federation play an important role in developing and promoting best practice for competitive and sustainable agricultural sectors.

NRM awareness, connection and participation of individuals from both the Mallee and beyond is promoted and advanced by a wide range of special interest groups such as Sunraysia OzFish Unlimited, WaterWatch, Friends of Kings Billabong, Mid Murray Field Naturalists, BirdLife Mildura, and the Victorian Malleefowl Recovery Group. These groups play an important role as a means for individuals to become engaged in activities and programs that reflect their particular interests or concerns. They also provide the region with vital sources of knowledge and understanding on specific issues through the local expertise that members hold, and the citizen science based monitoring programs that several groups undertake.

Collectively, the capacity of these groups and individuals represents an essential regional asset; with positive and long-lasting NRM outcomes dependent on an active, willing and capable community.

It is also recognised that while co-operative and community-based approaches to NRM ultimately benefits the condition of our natural, productive and cultural landscapes (and the environmental, social and economic values associated with these); the skills gained and the strengthened social networks achieved through participation also provides for increased community cooperation, mutual respect, sense of place, and education.

This section provides an overview on the current condition of Community Capacity for NRM in the Mallee. State-wide and regional indicators have been applied to establish a baseline, and where available identify long term trends, from which progress against our medium-term (6-year) and long-term outcome targets for Community Capacity for NRM can be determined.

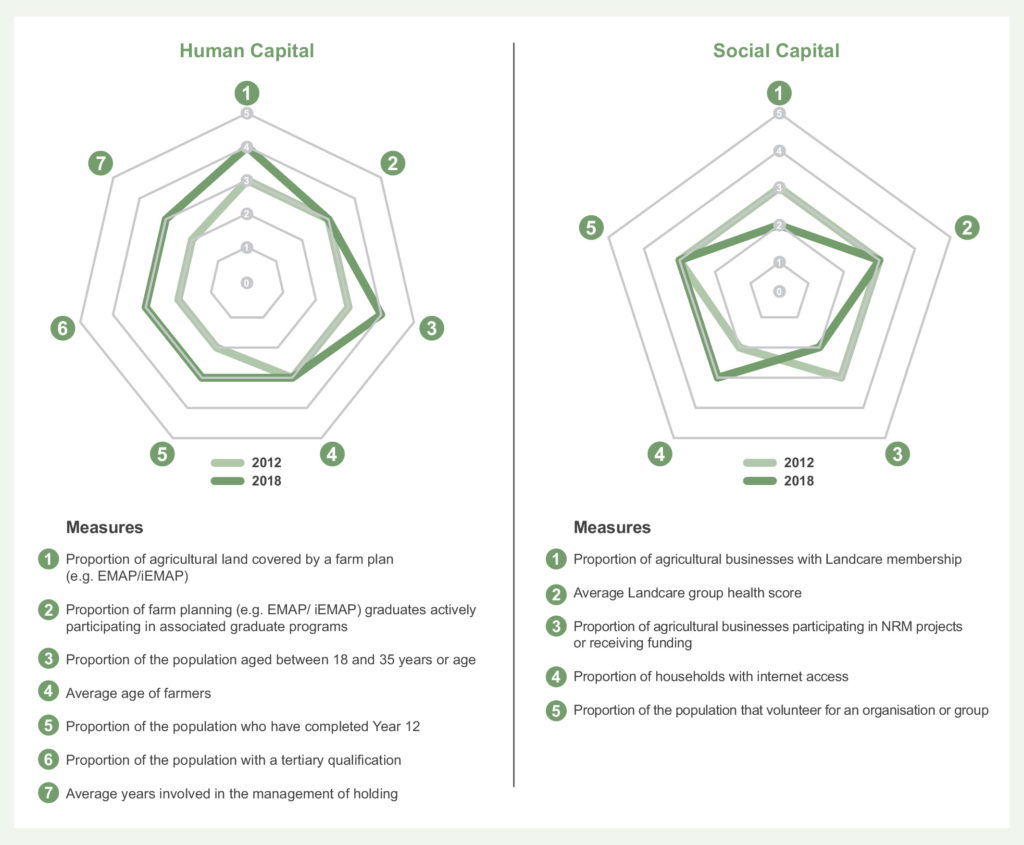

Historically, no regional-scale information has existed from which condition assessments of the Victorian Mallee community’s capacity for NRM could be made. This information gap was addressed as part of the Mallee RCS (2013-2019) MERI framework through the development of a Regional Community Capacity Monitoring Tool. This tool provides a measurable and repeatable assessment of the condition of community capacity for NRM at a regional scale. It is based on the Rural Livelihoods Framework, which identifies Community Capacity for NRM as a combination of human, social, natural, physical and financial capital. Scoring criteria have been assigned to each measure identified across the five categories of capital. Based on the data, each measure is scored on a five-point scale, where one indicates ‘low capacity’ and five indicates ‘high capacity’.

The Regional Community Capacity Tool was applied during 2012–13 to collect baseline data from which scores for each of the five capitals were assigned. This assessment indicated that, overall, our community has ‘medium’ levels of capacity for NRM in the region. Re-application of the tool in 2018 identified that at a regional scale, community capacity has remained relatively stable over the six-year period; with a ‘sustainable rural livelihood’ maintained, indicating resilience which is key to both livelihood adaption and the ability of the community to effectively manage the natural resource base for both production and environmental outcomes (55) (Figure 37).

Some fluctuations have however occurred at the indicator level. While all indicators of human and financial capital moved in a positive direction, two of the five social capital measures showed a slight decline, specifically, the ‘proportion of agricultural businesses with Landcare membership’ and ‘proportion of agricultural businesses participating in NRM projects or receiving funding’.

Participant evaluation surveys can also be a useful tool to provide assessments on the ‘effectiveness’ of community engagement activities and some measures of community capacity, supporting adaptive management continuous improvement processes.

For example, Mallee CMA apply a consistent evaluation framework (Targeted Community Capacity for NRM monitoring tool) to all engagement activities to allow data application at a range of scales (e.g. program, landscape, whole of region). Key findings from 2020–21 surveys included (56):

- Engagement event (e.g. workshops, field days, forums) participants identified ‘learning about a topic’ as their primary motivation for attending (70%), and a further 10 percent as ‘contributing to a discussion’. Survey respondents also reported a 36 percent (average) increase in their awareness of specific NRM issues as a result of participation, and a 19 percent (average) increase in skills to ‘address threat processes’

- Participants in tender and incentive programs delivered over the past five years initially identified ‘addressing priorities within my Farm Plan’ (47%) as the primary reason for seeking support to undertake works. On completion, however, the ‘desire to contribute to the general environmental management of the region’ (39%) was the highest reported motivation. Increased awareness of key threatening processes, and an increase in skills to implement associated mitigation actions were also reported.

Community Volunteering

Volunteers provide significant contributions to regional NRM efforts, through both formally organised activities and their individual everyday actions. There are currently some 50 volunteer-based groups in the Mallee that support delivery against the objectives of this RCS.

Landcare represents the largest volunteer network in the Mallee, comprising 25 individual groups with some 500 members. The Landcare movement has been instrumental in harnessing and promoting the interests of local communities in NRM since our first group, Millewa-Carwarp, was established in 1989.

Landcare groups complete group health surveys as part of the Victorian Landcare Grants program delivered by Mallee CMA. The survey provides a snapshot of the capacity of the region’s Landcare groups to participate in NRM over time. While there has been variation in average group scores over the eight-year period, ranging from 2.8 in 2017–18 to 5.2 in 2018–19, results generally indicate a ‘moving forward’ to ‘rolling along’ assessment (Table 11).

Partnerships

The number of formal partnerships established and maintained between organisations, Traditional Owners, community-based groups, and individuals contributes to our understanding of the extent to which NRM partners are working collaboratively towards achieving regional outcomes. A partnership is defined as an association of two or more organisations/individuals that has been formalised in writing; including arrangements such as memorandums of understanding, committee/working group terms of reference, and funding terms/conditions.

Data presented in Figure 38 represents partnerships established and/or maintained to deliver Mallee CMA funded programs over the past six years. It does not however capture the significant collaboration formalised under regional partnership arrangements delivered through other (non-MCMA) funding initiatives (57).

An important component of these partnership arrangements is supporting the region’s volunteer-based groups and individual land owners to undertake actions that deliver against both regional outcomes and their local priorities, objectives and aspirations.

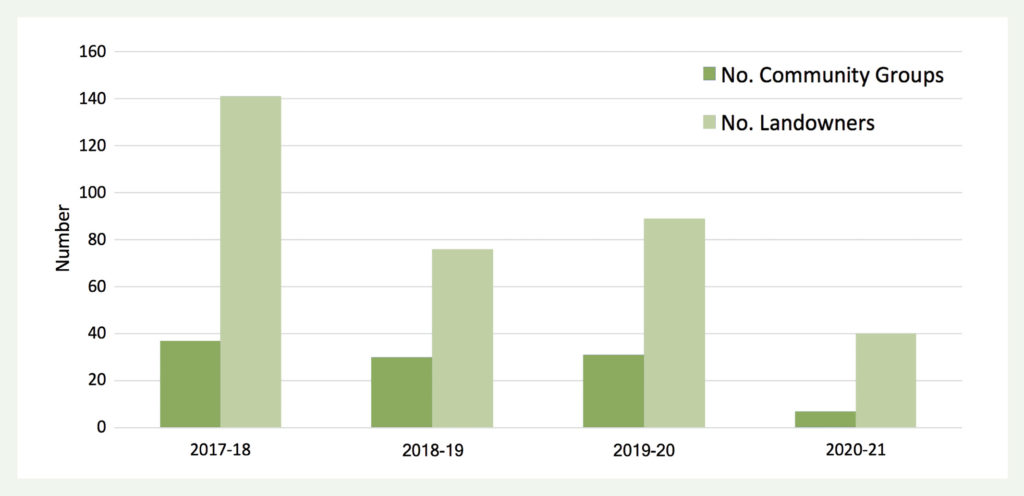

Figure 39 shows the number of grants provided to community groups and individuals under Mallee CMA managed programs over the past four years (58).

Delivered through state (e.g. Victorian Landcare Grants, Our Catchments Our Communities) and federal (e.g. Regional Land Partnerships) initiatives; grants have traditionally been utilised for actions such as revegetation, pest plant and animal control, stock exclusion fencing, citizen science programs, and irrigation system upgrades. Actions on private land are subject to public/private cost benefit ratio assessments to determine suitability and associated cost sharing arrangements.

These programs support stewardship outcomes that go beyond basic duty of care; providing environmental, economic, and social benefits at a local scale. They also provide participants with capacity building opportunities through their involvement in associated planning, implementation, and evaluation activities.

(55) RMCG (2018) Mallee Regional Community Capacity for NRM: Detailed Condition Report for the Mallee CMA.

(56) Mallee CMA, unpublished data (2021).

(57) Addressing this information gap will be required under this RCS to support monitoring and reporting of progress against associated outcome and management targets.

(58) While the number of grants is directly influenced by associated funding initiatives; delivery in 2020–21 was reduced in response to COVID-19 health orders.

This section outlines the major threats and drivers of change influencing the condition and management of Community Capacity for NRM in the Mallee; core management and strategic directions that will guide delivery of our related actions over the next 6-years; and the associated regulatory, policy and planning framework that informed their development.

Major threats and key drivers of change

Processes impacting on the Mallee’s Community Capacity for NRM are often a result of external drivers such as population dynamics and climate change. The impacts of these processes are wide-ranging and complex, and in many cases are outside the scope of this RCS to directly influence.

Through RCS delivery we can however support Mallee communities to build the capacity required to identify and implement effective management responses to these pressures. This includes recognising opportunities to enhance regional partnership approaches, and to improve how we collaboratively plan for, and deliver NRM.

In identifying future approaches, it is essential that the aspirations and concerns of regional stakeholders be considered, and where possible, incorporated into the priority management actions and desired outcomes set out by this RCS Community Capacity for NRM theme.

Key points and common themes identified by the Mallee community as directly influencing their participation in NRM, as impacting on the effectiveness of their efforts, and as potential opportunities for improvement are outlined below:

- Climate change is widely viewed as a critical issue facing the Mallee. Planning for these expected changes by identifying and implementing climate-ready adaptation options (e.g. providing habitat restoration for biodiversity migration) and improving knowledge to generate greater capacity for individuals and stakeholders to respond to pressures arising from a changing climate should be a priority

- Concern regarding the ability of the region’s agricultural systems to respond to climate variability and a changing climate. It is recognised that while there has been widespread change in management practices across both dryland and irrigated agriculture over the past 20 years, further attention and support is required to accelerate the identification and application of practices that are sustainable under all climatic conditions. This includes limits to water availability for irrigators and the impacts of increased drought risk on rural communities

- The growth of urban areas at the expense of rural population continues to present challenges in sourcing the necessary co-investment of time and resources from a diminishing (and ageing) population of rural landholders and community-based NRM groups. There is concern there will be insufficient people on the ground in large parts of the region to help deliver NRM focused activities. It is essential that the capacity of rural communities is recognised at the planning stage, and that adequate support mechanisms are established where necessary. Reducing the administrative load required by government funded initiatives is an area identified by many of our volunteer based groups

- Applying technology to engagement and communication approaches may assist in overcoming participation barriers often experienced by rural communities (i.e. distance and time). It should also be recognised however that while the number of online communities and applications is growing, digital connectivity and literacy can impact the uptake of such technology. Connectivity varies significantly across the region, with many ‘black spots’ across more remote areas. Enhanced connectivity, together with increased awareness of the efficiencies that new technologies can provide will be important factors in influencing effective application across the Mallee

- Protecting and enhancing the recreational opportunities and connections to nature provided by natural landscapes is important to many communities. Further support is sought for infrastructure that provides for increased activity (e.g. walking, boating), social connections (e.g. community events), and economic opportunities (e.g. tourism)

- Increased understanding of how land managers can participate in emerging carbon markets is required, along with the requirements and impacts (both positive and negative) of associated activities

- While there is general recognition that targeted NRM delivery frameworks are required to identify where ‘best’ results can be achieved with available resources (i.e. asset value x threat impact x intervention effectiveness assessments), support is also required for actions that deliver against locally significant and culturally important issues that may not rate highly within whole-of region asset-based approaches.

There is a growing recognition of Traditional Owners’/First Nations Peoples’ self-determination rights and their role in NRM. There is also a commitment among Governments to elevate Traditional Owners’/First Nations Peoples’ role in the policy, planning and management of Country. Feedback provided at workshops, meetings and on-Country events with Traditional Owners/First Peoples on how the RCS can support capacity building outcomes and help advance self-determined participation and leadership in NRM is outlined below:

- Cultural Heritage protection is a really important aspect of integrated catchment management (ICM), but it is just one aspect. First Nations communities’ interests in participation and engagement in ICM and partnerships with CMAs and other organisations across this sector are much broader than just Cultural Heritage protection

- ICM can be a platform for activities that contribute to self-determination and nation-building by First Nations communities

- Partnership-based activities have a direct benefit in themselves in terms of rehabilitating particular places, but these activities also have that broader impact of highlighting the role and responsibilities of First Nations peoples in managing Country, and contributing to health and wellbeing in community

- Two-way learning and ongoing collaboration in planning and management is vital. Bridging knowledge through co-design (understanding and applying Indigenous and scientific knowledge) will help strengthen partnerships between First Nations Peoples, landholders, community groups and other organisations; providing for better outcomes across the region

- Opportunities to reconnect to Country are essential; reconnection can happen in lots of different ways and mean different things to different people. This includes preserving and reviving language.

Integration of stakeholder and Traditional Owner/ First Peoples aspirations and priorities into regional delivery models will: assist in effective engagement; better support participants build capacity in NRM; and ultimately facilitate progress towards the region’s desired outcomes for Biodiversity, Waterways, Agricultural Land, and Culture and Heritage.

Further detail on the challenges, opportunities and major threats influencing Mallee NRM is provided in Section 1 (The Region – 4: Key Drivers of Change).

Aligned plans

Identification of the priority management and strategic directions detailed below has been informed by: federal and state legislation policies and strategies; regional strategies and action plans; and stakeholder priorities. The primary federal, state and regional instruments considered through this process are detailed in Appendix 2.

There is currently no overarching ‘whole-of-region’ plan that collates strategic directions, priorities and targets for building Community Capacity for NRM in the Mallee. For the purposes of this RCS, the following state government strategic frameworks were applied, where appropriate, to help inform our regional approach:

- Our Catchments Our Communities: Building on the Legacy for Better Stewardship; identifies three overarching objectives to deliver against the long-term outcome of ‘active catchment stewardship to improve catchment health’: strategic directions set by RCSs; delivery of better stewardship; and effective partnerships and improved capacity. Central to these objectives

is working with and investing in landowners and communities to deliver place-based on-ground stewardship projects for biodiversity, water, land health and productivity benefits - Victorians Volunteering for Nature: Environmental Volunteering Plan 2018; aims to have five million Victorians acting to protect the natural environment by 2037. Key actions to support this outcome and overcome barriers to participation include: making administration easier; building capacity and capability; improving sector collaboration; involving more young people; attracting more diverse volunteers; harnessing technology; partnering with Aboriginal communities; and celebrating and promoting volunteering

- The guiding principle for Traditional Owner participation and leadership in NRM, is self-determination. This is described in DELWP’s Pupangarli Marnmarnepu ‘Owning Our Future’ Aboriginal Self-Determination Reform Strategy 2020–2025, which aligns with whole-of-government commitments set out in the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework (VAAF) and the VAAF Self-Determination Reform Framework; which guides government and agencies to enable action towards Aboriginal self-determination. From an NRM perspective, this means empowering Traditional Owners to participate and lead, if and how they choose; efforts to manage and heal Country.

Community Capacity related planning frameworks and priorities that focus on specific landscapes (i.e. not whole of region) are identified within their associated ‘Local Area’ (see Section 4). This includes Traditional Owner Country plans, individual NRM Groups’ plans, and individual theme and or landscape based planning.

Management directions

In considering the current capacity of Mallee communities to participate in effective NRM, key drivers influencing this capacity, associated planning instruments, and stakeholder priorities; seven key principles to direct future actions have been identified. Specifically, that capacity building focused programs collectively support:

- Increased awareness and appreciation of the Mallee’s natural, cultural and productive landscapes

- Increased understanding of Mallee communities and key drivers/barriers influencing their participation in NRM

- Responsive and effective stewardship of our natural, cultural and productive landscapes

- Participation in NRM by landholders, community/ Traditional Owner groups, and volunteers; including the establishment of effective support mechanisms as required

- Recognition and celebration of, and respect for Aboriginal culture

- Identification, and where appropriate, development and implementation of effective responses to emerging threats and opportunities

- Co-operative and coordinated approaches to NRM that support multiple/landscape-scale outcomes.

In developing programs to deliver against these principles, the following priorities have been identified to inform how our actions are planned and implemented:

- Tailored/targeted education programs promoting the Mallee’s natural, cultural and productive landscapes; and actions contributing to their protection and enhancement

- Supporting private landholders to protect/enhance their biodiversity, waterway and agricultural assets; including through the provision of financial incentives and/or other market mechanisms (where appropriate) that offer options suited to different landscapes, motivations and outcomes being sought

- Supporting community and Traditional Owner groups to participate in NRM programs, including through the provision of financial grants (where appropriate) to deliver against local/regional priorities

- Supporting, valuing and promoting the contribution of volunteers from both the Mallee and beyond

- Citizen Science programs that engage community and provide targeted data to inform NRM programs

- Providing opportunities for people to connect with nature

- Providing opportunities for Traditional Owners/First Peoples to connect and spend time on Country

- Respecting the value of traditional knowledge, and the right of its custodians to determine if/how it is shared and used

- Regional and local partnerships that provide for co-operative approaches to NRM planning, delivery and evaluation established and maintained

- Approaches that generate greater capacity for all stakeholders to respond to pressures arising from a changing and variable climate.

Priority directions for the protection of Traditional Owner/ First Peoples cultural values are outlined in Section 3.5 (Culture and Heritage).

Strategic directions

The capacity of Mallee communities to effectively participate in, deliver, and lead NRM programs is shaped by a diverse and complex suite of factors, many of which are outside the scope of this RCS to directly influence (e.g. changing demographics, climate change).While biophysical assets utilise a prioritisation framework, where the value of the asset x the impact of threatening processes represents a key consideration in targeting delivery; the Community Capacity for NRM asset has no standard analyses to differentiate relative value.

Given the finite resources available to the region to undertake community capacity focused programs, it is not feasible to expect that all identified actions can be applied at a whole-of region and/or stakeholder scale over the life of this RCS. To help ensure that effort is directed to actions that will ultimately progress the region’s desired outcomes and vision for community capacity, six strategic directions have been established to assist in the prioritisation of regional programs. Specifically, that the proposed actions deliver against one of more of the below priorities:

- Build the capacity of landholders, community groups, Traditional Owners and individuals to support regional NRM efforts

- Support and respond to the evolving needs of landholders, community groups, Traditional Owners and individuals already participating in NRM

- Facilitate opportunities for broader and more diverse participation in regional NRM efforts

- Advance opportunities for self-determined participation and leadership by Traditional Owners

- Support delivery against regional priorities for biodiversity, waterways, agricultural land, and culture and heritage

- Support delivery against locally significant and culturally important issues.

This section outlines the medium-term (6-year) and long-term (20-year) outcome targets that regional stakeholders have collectively set for Community Capacity for NRM across the Mallee.

Our medium-term outcome targets have been developed to align with, and demonstrate how, the Mallee RCS will contribute to state-wide and regional indicators (59).

Delivery against these targets will be undertaken as part of the RCS’s ICM – landscape-scale approach to NRM (Table 12). Detail on the specific management actions and targets to be implemented within individual landscapes, and the local stakeholders that will contribute to their delivery is provided in Section 4 (i.e. Local Areas).

(59) No regional scale baseline information is currently available for three of the eight stated medium-term outcome targets (i.e. increased number of opportunities for Traditional Owners/First Nations Peoples to reconnect to Country; increased number of formal partnership agreements between Traditional Owners and key NRM agencies; increased number of programs that are co-designed and implemented in partnership with, or led by, Traditional Owners) at a whole of region scale. This information gap will be addressed though the RCS MERI Framework, with the establishment and ongoing measurement of associated indicators.